The Amadeo Chest (or in Praise of the Archive)

(The joy of being at this table, with Delfim [Sardo], makes us both realise that behind all curatorial work lies time, research, preparation, questioning, a point of view. And almost always, the ‘archive’, whatever form it may take, is the protagonist.)

Let’s start with the words: ‘documentary estate collection’, three words that, when placed together, suggest a static weightiness (their sound itself is heavy). For those who have never worked in an archive, the word itself may conjure up nightmarish images of sinking.

I’m here to bear witness to the opposite.

When, 22 years ago, in 2000, the then director of CAM, José Sommer Ribeiro, took me on to coordinate the Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso ‘Catalogue Raisonné’, and placed the task of unearthing this estate collection in my hands, I could never have imagined how far this project would take me, how an archive could be a trigger for movement, a persistent flight, an irresistible adventure.

The fact it was this artist in particular helped, I have to admit, but in this estate collection I immediately found the marks of lightness, speed, and so much more.

For almost a decade, accompanied by Catarina Alfaro (and also by Leonor Oliveira at various stages in the research), and by other co-workers who actively collaborated with us (such as Ana Barata, who is here in this room), we were held in the vertiginous state of standing so perilously close to the life of someone who was no longer alive. As we progressed over that immense sea of documents, a sky of questions formed, as if in a mirror.

We found some answers, that’s true, but even more importantly, we allowed ourselves to formulate many new questions, which await new teams and perspectives.

It’s important to stress that the artist did not intend for his documents, diaries, books, photographs, catalogues, loose sheets, notes, and more or less private letters to his mother, sisters, uncle Francisco, father, Manuel Laranjeira, many artists, and Lucie Pecetto (who would become his wife, the only love letters found) to be available for academic or historiographical consultation. Amadeo didn’t feel the need to arrange or organise (for posterity) details about his work, and his records don’t reveal any particular systematisation. All the documentation that has come down to us, through the various archives we have consulted, reflects a youthful disorder, the urgency of doing: ‘our life is all forward-facing,’ he said in a well-known interview in 1916. His programmatic written reflection is episodic, fragmented and residual, fragments of a life on the move, still without any retrospective vision.

Only his strategy of affirmation and publicity around the publication of the ‘XX Dessins’ appears to us as a premeditated act. And this is something to reflect on. All the care the artist devoted to this edition, not only in the choice of publisher, but also in the meticulous network of international shipments, transforms this album of 20 drawings, published in 1912, into a true and anticipatory portfolio. On the pages of his diaries or in his letters to Lucie Pecetto, we can see and analyse the laborious ingenuity with which Amadeo worked to ensure that this book reached the hands of the main agents and protagonists of the art scene of the time, in various capitals of the Western world. And with the return on that investment, in terms of his critical reception and future invitations, which we all already know.

An archive, processed, organised and made available, can be a powerful agent for transforming the historiographical and critical reception of artists and for the very construction of art history, which is under constant revision. The case of Amadeo is a special one. The artist, who died prematurely in 1918 and was eclipsed from history for decades, was covered in an auratic mantle of mythification, fuelled by a lack of knowledge about his life and work. Indeed, only the continued presentation of his work (after the inauguration of CAM in 1983) and the meticulous study of the various archives (from the Gulbenkian Foundation Art Library, family members, international archives, one leading to another) have made it possible to transform intuitions into facts and myth into reality.

I can give you some information that has been clarified and determined by the documentary estate collection:

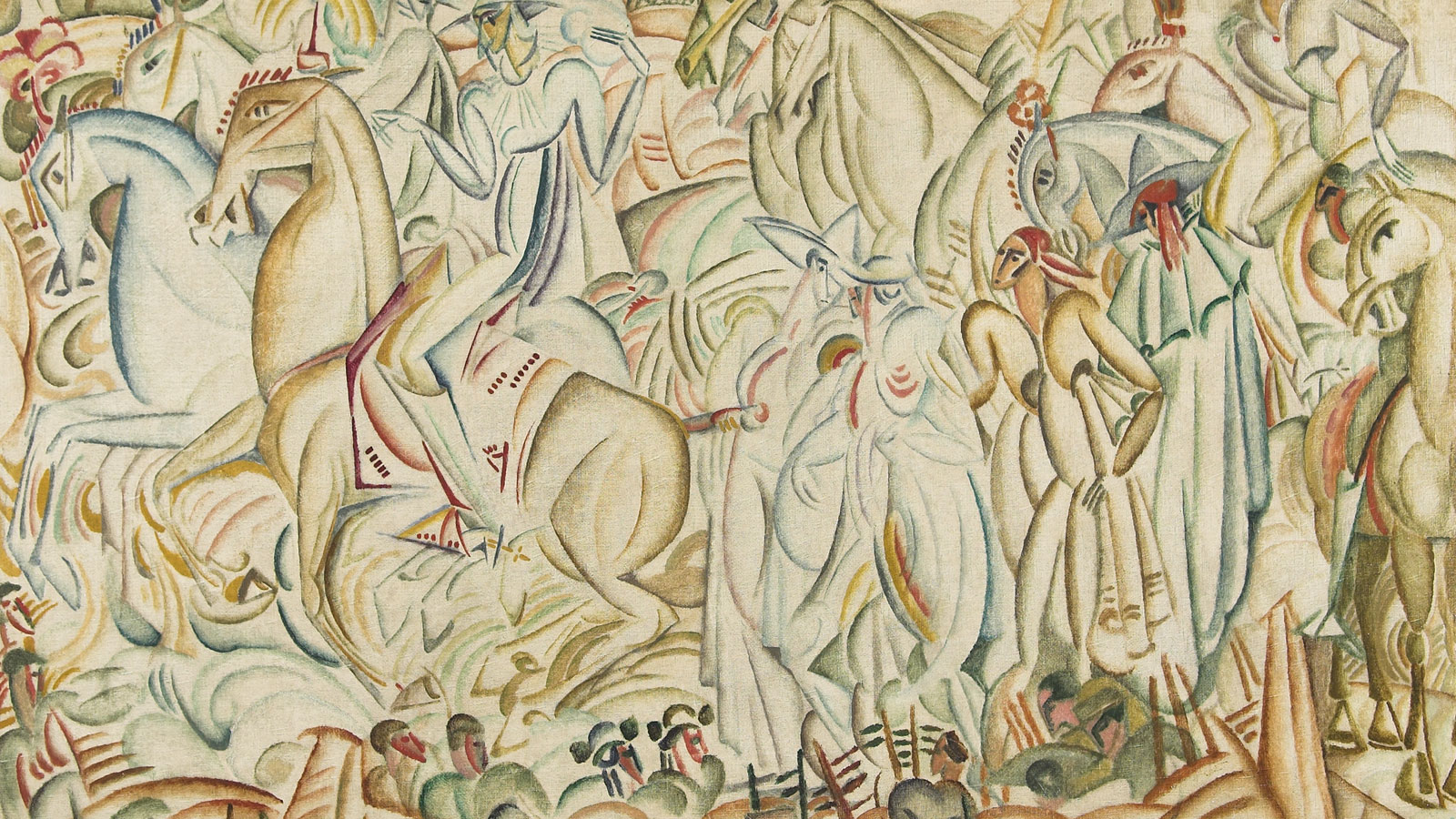

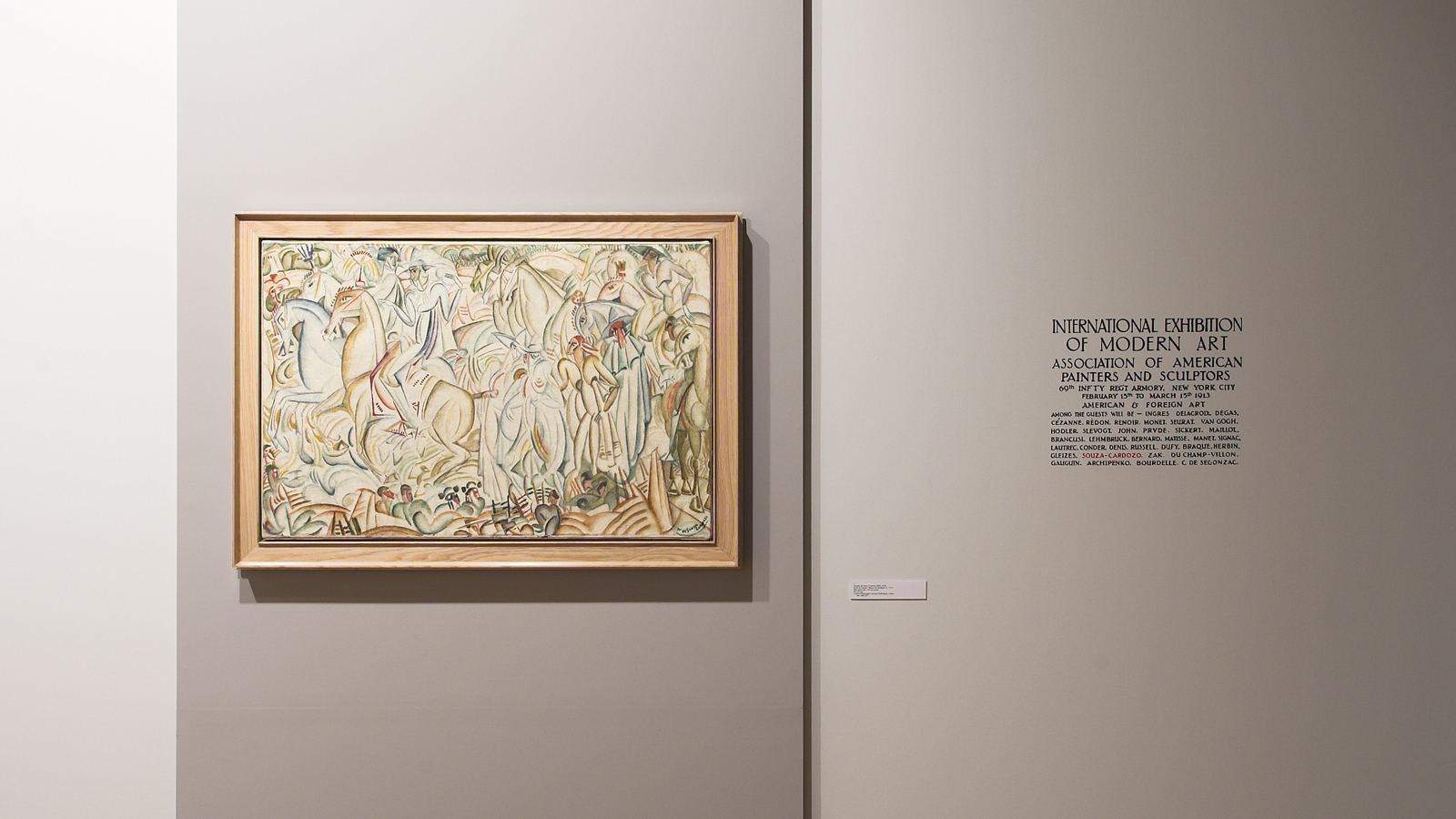

Yes, Amadeo was one of the artists to have enjoyed the greatest media, critical and market impact at The Armory Show in the USA, where he sold seven of the eight works he presented. In a critical review of this event, Frederick James Gregg (the publicity agent for the Armory Show) presented him as an artist that had been successful in Moscow and Berlin.

It was through Sonia and Robert Delaunay that he entered the ‘Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon, Der Sturm’, with three paintings, in 1913. He took part in the London Salon in 1914 and had contacts with Roger Fry. The network of friendships that linked Amadeo to Otto Freundlich, and he to Wilhelm Niemeyer (organiser of the Sonderbund), was essential for clarifying his artistic passage through Germany, refining it and deepening the understanding of his work from 1913 onwards: Berlin, Cologne, Munich, Hamburg.

Confirmation of his fame abroad also comes from the correspondence he exchanged with some of the artists and protagonists in the field with whom he maintained close friendships, such as Amedeo Modigliani, Constantin Brancusi, Otto Freundlich, and Walter Pach. The intensity and turbulence of his relationship with the Delaunays is also well known, from Paris to Vila do Conde. Amadeo familiarly names Umberto Boccioni, Guillaume Appolinaire, Blaise Cendrars, Marie Laurencin, Albert Gleizes, Alexander Archipenko, and Pablo Picasso. Indeed, Amadeo lived naturally among his peers as an artist of the world, between Manhufe and Paris (between the city and the mountains), and all these facts are documented.

I remember how important it was never to lose sight of the works, not to get lost in the narrative mesh of his life. The parallel tracing of these two paths, which are permanently intertwined and make up the artist’s body, was fundamental.

I can offer the question of titles as an example. One of the rewarding aspects of this research was the recovery of countless of the artist’s original titles and the correction of many others, obtained by exhaustively cross-referencing documentary information with direct observation of the works. This aspect is all the more important because it embodies the true identity of the works. From the catalogues that have come down to us (through the estate collection or the various clues it left us), of the works exhibited or published during the artist’s lifetime, we know with certainty that Amadeo always named the works he exhibited. What’s more, these titles, especially after 1915, reveal a composition and graphic sensibility in pieces drawn by the artist himself and which he had faithfully reproduced, and which correspond to an aesthetic and authorial attitude, explainable by the Futurist or proto-Dadaist context in which they were realised. It’s important to bear in mind that the experimental and anticipatory quality of his work also comes through here, a fact that can only be confirmed by documents.

And I can’t help but mention this as a structural and obvious fact: it was from the estate collection, from the cross-referencing of names in diaries, letters and photographs of works, that we arrived at some of the lost works that have been subsequently located. One of them is ‘Avant la corrida’, a work that had been missing since it was sold at The Armory Show in 1913, a photograph of which was posted on the Gulbenkian website, until it came to the attention of its American owner, the heir to a painting by an artist he did not know. This painting has since become part of our art collection.

Throughout this project, I’ve realised that we shouldn’t neglect the biography of artists, the projections of their identity, and that what may seem accessory, circumstantial or accidental, can end up echoing and reinforcing the meaning of their works.

In Amadeo, the echoes between life and work are many and evident. The artist’s discourse is not linear; he moves nimbly through the unexpected, in the ‘Saut du lapin,’ in zigzags, difficult to imprison in codes, schools, timelines, categories, orderings, thus constituting himself and resisting any alignment raisonné. ‘I have more phases than the moon,’ he used to say, disdaining all those schools that sought in his time to organise the isms of the avant-garde’s ruptures. His work fuses the cosmopolitanism of Paris with the vitality of the mountains. It does not offer a single meaning; the nature of his work is polysemic.

We find a little of all of this in his estate collection too. In the versatility of the unstable handwriting, the disconcerting layout of the signatures. In the geographical impermanence, in the insatiable desire to always be where he is not, in the multiple studios he rented in Paris (seven in all over the Parisian years), in the deeply plural image he built of himself, as plural as his work. I’ll pass on this gallery of ‘quasi’-heteronyms, which point to some complicities with his contemporary Fernando Pessoa (who described Amadeo as the ‘most celebrated Portuguese advanced painter’).

Amadeo was a family man, a landowner, provincial, proper, a horseman, a guitar player, a rogue, a traveller, a painter in a beret, a peasant in sandals, in the centre of the studio, or again a horseman, a bohemian à ‘los Borrachos’, a gardener, a cosmopolitan, almost always looking down from above, a high-angle perspective, with his gaze focused, from a very young age.

As we know from his estate collection, Amadeo was a photographer, capturing the rural landscapes he sought to represent and experimenting boldly in this discipline, superimposing images and creating a small body of work which he never gave public space to (Margarida Medeiros reflected on this in 2016 at the Grand Palais exhibition). As in so many other areas, it’s pointless wondering what may have become of these forays had he lived on.

And as a final example, he also left us an enigmatic element in his estate collection, a photograph of a working model (or a work?) that seems to have served as the basis for developing various solutions in his last known works, manipulating the constituent elements of this object, tambourines, collages of advertisements, folk dolls, zigzagging threads (Picasso is known to have used similar models).

The vast contents of this chest allowed us to elevate this seemingly heavy material, tending towards immobility, and to outline a strategy of great movement.

Without it, little would have been possible.

I’ll go over some of the key events that led us here. Back in 2006, when it was impossible to complete the ‘catalogue raisonné’ in the immediate term (so many issues with forged works), we embarked on the adventure of creating an exhibition that would allow us to SEE, through the works, the true ‘Dialogue of the Avant-garde’ that Amadeo experienced, through the artists with whom he crossed paths as an artist, not a follower. With this exhibition, and the movements and contacts it provided among museum directors, curators, couriers, international curiosity about the artist was rekindled and the momentum for new invitations to international exhibitions, both group and solo, eventually arrived. As early as 2008, at the Ernst-Barlach Haus in Hamburg, a city where the artist had already exhibited, and several others. I won’t go into an inventory, to which we’ll always have to add other initiatives by other artists and institutions. In the meantime, and to close, now armed with a set of editions launched as part of this project, Amadeo’s ‘Photobiography’, the ‘Painting Catalogue Raisonné’, the facsimile of the ‘Legende de Saint Julien l’Hospitalier’, considered by many experts to be one of the most unique and daring works of its time (1912), we were able to arrive at the Grand Palais (with the security of carrying serious research in our arms) and propose a solo exhibition in Paris in 2016, a century after the artist was exhibited in these same rooms at the Salon d’Automne in 1912. I’ll never forget the astonishment of the then director Laurent Salomé (now director of Versailles), leafing through the heavy volumes and seeing for the first time the powerful works of an artist unknown in Paris, nor the question (very French…): ‘But who is this artist that I do not know?’

The time was (is) favourable to us, conducive to a focus on peripheral modernisms, plural modernities (Catherine Grenier at the Centre Pompidou), already far removed from the hegemonic readings of the past. Amadeo continues on his path to international recognition, but our work must be persistent and ongoing so as to avoid the stubborn cycle of intermittence in Portuguese art history.

As an art historian working on this project, I can assure you that it is extraordinarily difficult to add a piece to a historical puzzle that has already been constructed and formalised. It’s a resilient matter. For Amadeo and for many artists of various generations who were and still are victims of the silence of a country that for many decades closed itself off from the world, I insist that this is a moment of openness to new, plural perspectives on art history and artists.

Research snowballs, growing as it rolls down the mountainside and feeds on chance and sediment. It makes old artists grow and drags new ones into its orbit.

And the adventure continues.

While I was writing this speech, a friend sent me a short poem, dated the day of Amadeo’s birthday, a very close friend who knows the (still secret) shortcuts of a new adventure that is being prepared, once again in Paris. I leave you and conclude by reading these words:

‘his mother would have written to him, his uncle (and perhaps his sisters too)

so that the letter would reach him quickly,

as close to today as possible.

But the train was more than a century late

and only now are the letters and paintings starting to arrive,

the shadows and voices of scattered friends

are only gathering today.’

Paris, 14.11.2022