‘I think young people are looking for representation. They want to see themselves in the museum.’

What made you want to take part in the Youth Advisory Group? What were you expecting when you applied?

I had just finished my Bachelor’s degree, but I didn’t feel ready to start my Master’s. It seemed like a lot of responsibility, and I find continuing along the same path very boring. I was a bit fed up with studying.

When I saw the ad, it really spoke to me because it had to do with young people. It seemed to be calling for people to make changes to the museum. I had always seen Gulbenkian and other cultural institutions as rather stuffy, intransigent places. I wanted to understand whether they really wanted to know what we were thinking. I thought it would be a bit like doing a postgraduate course, but without all the deadlines.

That’s what caught my attention, as well as wanting to understand how such a large institution seemed prepared to put so much trust in people who hadn’t yet turned 30.

You’ve said that you used to think the Gulbenkian and other such institutions were rather stuffy. Tell me a bit about that.

I only learned about Gulbenkian when I went to university. I thought, ‘How come I never heard about this massive institution when I was at school?’

In my head, museums were highly paternalistic. ‘I’m your father and these are my children. Everything in here is mine. I own it. I’m in charge. I say what it is and what it isn’t.’ Of course, it’s likely that the things inside the museum don’t correspond to the definition that they give them.

I think a lot about the MNAA-Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, which has a lot of things from Africa and Portugal. But who’s to say that things are really as the museum has defined them to be? So I feel as though I’m always on the back foot, as it’s like there’s just one perspective, but I need to understand all the possible perspectives in order to form a final opinion.

The school gave me the idea that we go to the museum and we get a guided tour from someone who has already studied the pieces and tell us about them from the artist’s perspective. And it’s definitely important to get the artist’s perspective, but there are things that go well beyond the artist’s vision.

What do you think young people and young audiences want from a cultural institution?

I think young people are looking for representation, they want to see themselves in the museum. It’s disquieting to visit a place and identify with absolutely nothing there. You see things you’ve learned about in school, and it’s like you’re simply reinforcing that lesson.

Visiting a museum and feeling that it’s concerned with the issues of today is essential, because it shows that they’re empathic and not trying to dodge the issues. I feel that people aged between twenty and thirty are especially concerned about what’s going on in the world today.

When I lived in Sintra, going to a museum was the very last thing I would ever think of doing, because I knew it would just be another history lesson. If I had known that the museum was also talking about my history, about being of African descent, about being a woman, about being black… Those things would properly speak to me.

The first exhibition I saw at Gulbenkian was ‘Europa, Oxalá‘. Why? Because it talked about artists of African descent and their journey. It showed works by black people. Rather worryingly, that was something I had never seen before. I was 20 when I went to see the exhibition, and that was the first time that I had ever seen works by black people in a museum. The themes of the exhibition sparked a sense of familiarity in me.

I felt comfortable in the museum. That was the way I wanted a museum to be. It addressed the issue of colonialism, it featured this work by Márcio Carvalho… CAM’s interest in these themes is very encouraging. I feel that I can be present here, that I belong here too. It doesn’t matter where I’ve come from, it just matters that I’m here now.

That’s what I and people around me feel when it comes to the lack of representation or emphasis on these issues at museums. Can museums really remain indifferent to these things? I believe that talking about these issues brings a more human dimension to the institution. And it’s not just about talking, but about bringing people from completely different backgrounds in so that they can express their reality.

To go back to the Youth Advisory Group, how has it been working together?

It’s been great. It’s been something of a change for me, because although I’ve always worked in groups, this one has a mix of different disciplines. We have people from the worlds of history, dance, theatre, science, you name it. Fascinatingly, we’re all more or less the same age, but we have very different perspectives. Despite those differences, we don’t clash and we always try to find a compromise, that grey area between our opinions. There hasn’t been any conflict at all so far.

I think that people were really hand-picked for the Group. Some of us are from poorer backgrounds, others from wealthier backgrounds. There are academic high-fliers and those who failed at school. Some are shier while others outgoing. I think this mix of personalities and backgrounds is the key to reaching out to young people, or rather finding ways to appeal to young people. I love that we’ve been tasked with thinking about what we can do to get young people to come and visit the museum.

You’ve also had a number of sessions with CAM’s different teams. What has made the greatest impression on you so far?

The Education Services team impressed me the most. Margarida Vieira Mendes, who works with people with specific educational needs, used an onion as an analogy for her work at the Gulbenkian. The first thing I thought of was the line from ‘Shrek’ – ‘Ogres are like onions!’ We are onions with many layers. In order to understand why we are the way we are, we peel away those layers.

I love this element of the Education Services mission, as the team cares so much about the general public and understanding why they are visiting or not visiting, and tries to identify what makes people feel as though they belong or don’t belong. They could easily not bother with all this or not provide an education service at all, but instead there’s a real enthusiasm and desire to understand how the public feels, what stage of life they are at, whether they are at school, working, whether art is relevant to their lives, and so on.

From the moment that art became my way of life, my confidence and ability to converse improved and I felt much happier. The discussion of the onion made me see that the Education Services team and the Gulbenkian Foundation really do want to know why people want to come here or not, and by peeling away the layers of the onion one by one, they will get to the bottom of it. Art is often disregarded by many people, but the Education Services are showing the benefits of having art in your life.

Speaking of the impact of art on people’s lives, could you tell us a little about the project you were involved in and which you describe in your application letter for the Youth Advisory Group?

ParteJ – Artistic practices for youth empowerment was a project carried out by the Chão de Oliva cultural outreach centre in Sintra.

Previously, I saw Sintra as a place devoid of culture. As far as I was concerned, there was no theatre, no music, no dance – nothing. I had got that impression from my routine of school to home, home to school, and that of my parents – work to home, home to work.

ParteJ came about at a time when my mental health was terrible. I was questioning everything – whether I should continue at university and carry on along my chosen path. Out of nowhere came an initiative offering completely free artistic activities, which was completely out of the blue in a place where art isn’t at all prominent.

The ParteJ project is aimed at young people aged 15 to 25 who have become turned off from education and feel that the system has little to offer them. It gives them the opportunity to discover that the arts can be an option for their professional lives. People have this idea that your primary schooling is your basic education, and then you specialise in secondary school. But it’s the journey from first to ninth grade that shapes you and deems you good or poor at maths, Portuguese and so on.

I’ve worked with children who felt they weren’t good at anything – drawing, Portuguese, mathematics or history – and if they weren’t good at any of these things, they felt excluded at school, because ‘If you get ‘Unsatisfactory’, you’re bad!’ School grades do a lot to define people.

We want to show that just as school is a pathway, the arts are also a valid route into the job market. These young people can access a bright future in the arts, and that doesn’t mean selling art on the street. ParteJ put on music, dance and theatre classes, which met with immense enthusiasm, firstly because the activities were free and secondly because they were led by professional instructors, not amateurs.

The project showed us how beneficial it can be to give young people the right tools and show them that the opportunities available to them. But we didn’t feel that it was enough just to give them free lessons. The regularity of the activities made the participants feel confident and comfortable, and created a certain intimacy, but there was no sense of comradeship between the people who belonged to ParteJ . The attendees of the dance classes only mixed with the dance people, while those in the music classes only got to know the other music people. I felt that the participants did actually want to get to know each other, because they shared a taste for art.

My assessment was that, yes, it’s nice to give things away for free and provide tools, but there was a need for a project with real continuity. So I invited the keenest ParteJ participants to join the ParteJ Collective. The aim was for them to create an cultural agenda of their own and grasp that museums are open to them and everyone else. ‘No, you won’t be an unwanted presence – you can come right in. This is a place for you to create and discuss art.’

We began by discussing thorny topics like the LGBT struggle, racism, being a woman and environmental issues like the gravity of climate change.

Then we moved on to constructing our cultural agenda, starting with Sintra. I was troubled to learn that the participants had never been to the National Palace of Pena, even though Sintra is only a ten-minute train journey from the Tapada das Mercês. They hadn’t been to the Park and Palace of Monserrate, either; in fact, they were completely unaware of its existence. They’d never been to the Quinta da Regaleira or MU.SA – Museu das Artes de Sintra , and they didn’t know that Sintra had a theatre company.

Sintra was the first stage in their journey. For me, it was like an exercise in self-discovery, because there was much more to the place where we lived than we knew. As I said to the young people, it would be very mistaken to think that a place doesn’t have any culture. It’s impossible not to have culture; the issue is that the information might not reach us in the same way as it does other people. I feel that Sintra’s cultural agenda is very high-brow. There’s opera, ballet and various other offerings of that nature, but it never quite meets the interests of young people.

We went to MU.SA and discussed the concept of feminine. We visited the Palace of Monserrate and talked about the issue of the Discoveries and the reason for the Arab artforms found in the Sintra area. On 25 April, the anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, we held workshops on screen printing. This was a first for the participants, who learned that it is often used to produce posters for demonstrations. We also went to some talks by Amnesty International. Through these activities, they started to see that they didn’t need to be at school to learn and have an opinion.

Finally, we created a lot of artistic objects of our own. They realised that they could be artists, create art and get other local people to enjoy art, too. They discovered that drama, music and dance are not just what school shows us, but so much more. They learnt that hip hop and street art are also authentic forms of art. Although they come from the street, they are legitimate forms of expression that they can relate to. They used to think that art was something lofty, superior and sophisticated, so what they saw around them couldn’t possibly be classified as art.

From then on, they began to see that it is possible to create, enjoy and shape our own cultural path, and that it doesn’t matter where we come from. We belong here – it’s our right!

After that project, you also took part in SenteMente, a Partis & Art for Change project [an initiative by the Gulbenkian Foundation and the ‘La Caixa’ Foundation to promote and publicise the civic role of participatory art and culture]. Could you talk a little about the power and importance of participatory art?

The power of participatory art can be compared to a baby starting to crawl. First we have to feel out the ground to understand the lay of the land and the people that we’re working with. Then comes the action part.

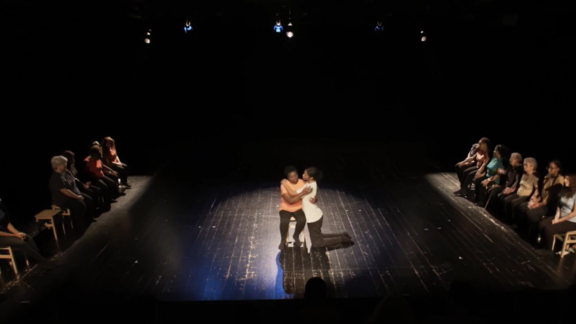

SenteMente was a project that saved me, and that’s no exaggeration. I’d just had an anxiety attack at university and I felt completely lost. When I joined the project I realised that participatory art awakens a side of us that we don’t know we have and can truly save us. Some of the other women involved were in a very bad way, suffering from depression, anxiety, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. But together, through art, we discussed these heavy issues in a much lighter way! The art also offered us a lot of scope for play, which often made us forget that we were going through our difficulties.

I believe that a participatory approach to art is ideal. All of school should be like this, without the imposition of hierarchies. It should be an ongoing exchange between instructors and participants, without the former telling us, ‘We know what’s best. Here’s what you need to do.’ With SenteMente, we created our own script. We decided which stories would go in, which stories wouldn’t, and whether we would take on a story or not.

I felt that SenteMente was the very essence of participatory art. More than just giving us a voice, it gave us the tools to let that voice out. We were all very fragile at that time, but the project left us in a much more comfortable place. It was a space to laugh, cry and tell secrets, because what was said there never left the room.

At the end of the project, we had the opportunity to show what we’d done, express what we’d experienced and raise awareness of the importance of mental health. It’s a prevalent issue, and a particularly delicate one for women. It hits disadvantaged women especially hard. They might be out at work from 6 am every day, where they are mistreated by their boss, before coming home and having to care for their children – often with their own problems – while feeling under constant pressure to be beautiful, act perfectly and all the rest of it.

I think that participatory art is the best way of healing our inner child, by creating an environment of equality where we are all on the same level, can exchange stories and show a genuine interest in other people and what they have to say.

I believe that Gulbenkian can only enhance its value by overseeing these kinds of projects, in addition to its creative and funding endeavours. It’s one thing just to give money, but it’s quite another to be on the ground and part of the process. The dedication that the team has shown has transformed by initial perception of a rigid institution and shown me a more human side to it.

Partis is a project that saves lives. At least, it saved mine. After Partis I became much more confident and I’ve never looked back. The world has taken on a different colour.

You were also part of the first group of guest artists curated by Dino D’Santiago for the Jardim de Verão festival. What did you think of the audiences who came to the events? Generally speaking, they’re not exactly the same groups of people who usually come to Gulbenkian. What did you think of the atmosphere and what did you take away from the experience?

Again, it’s a matter of representation. The poster featured all artists of African descent. Like it or not, most Lisbon residents of African descent live along the Linha de Sintra railway line, or on the south bank. Suddenly, Gulbenkian, which is a very white institution, was full of different people.

I knew the names of most of the people there. Most of the attendees were from Tapada das Mercês, Rio de Mouro, Rinchoa, Massamá. The festival was outdoors and we felt perfectly at home thanks to the warm weather and the warmth of the people.

I think it was the first time that some people from that area had learned of the existence of Gulbenkian, and even then they probably only associated it with the Summer Gardens, but that’s fine.

I loved that year. It was my first concert ever and I cried a lot at the end. I tried to hold it in, but I couldn’t. Like the concepts of Nova Lisboa and Lisboa Criola, which Dino also curated, what moved me was having such a diverse crowd at my first concert, with black people, white people, immigrants, a bit of everything.

Recently, I’ve been thinking how amazing it is to bring people to the garden, where we get to be outside, but the garden isn’t the museum. It’s great that people are coming to the Gulbenkian Garden, but it would be even better to make them see that there’s a whole lot more to see and learn inside. Not just the history of Europe, but also the history of Africa.

I hope that the next Jardim de Verão festival will be inside the buildings, so that people shed their fear about going in. I hope that the institution itself isn’t a barrier. It appears that many people see the building as a kind of wall. I don’t want people to come all the way from Sintra or the south bank just to be in the garden.

‘Come on in! This is for you. Yes, you might well find triggering things in here, but let’s work on those triggers and figure out what we can change. Feel free to voice your opinions. Tell us what’s right and what’s wrong.’

Bringing the Summer Gardens inside the buildings would be a good way to engage younger people, so that they realise that this isn’t just a mass of concrete and glass; it’s an institution with a face. It’s a safe space.

What are your expectations for the reopening of the CAM?

I think it’s going to be great. When we present the projects to the different teams, they really listen to us and are eager to know what young people want to see inside the institution. They’re very focused on integration. It won’t be just another museum;

it will be more participatory, a place where young people are welcome to come inside, to interact, talk and argue. I don’t know how it’s going to be publicised or anything like that, but I’m sure it will be a landmark event at the end of summer.