For me, ‘choreographics’ is poetry

He studied graphic design at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts in Paris, but it was when he entered the world of dance that Smaïl Kanouté rose to prominence. A curious adventurer, Smaïl’s eyes take on an almost childlike glow when he talks about his explorations and discoveries. But it is with mature enthusiasm that he speaks about his journey, about how he found and lives dance today, about his ear for music, about what he drew from religion, about the thirst he has to dive into stories and, above all, into his origins, which reside thousands of miles away. It is with maturity that he speaks of creation, colonialism, miscegenation. With so many adjectives, who exactly is Smaïl Kanouté? According to the man himself, he is a ‘creator of new perspectives’.

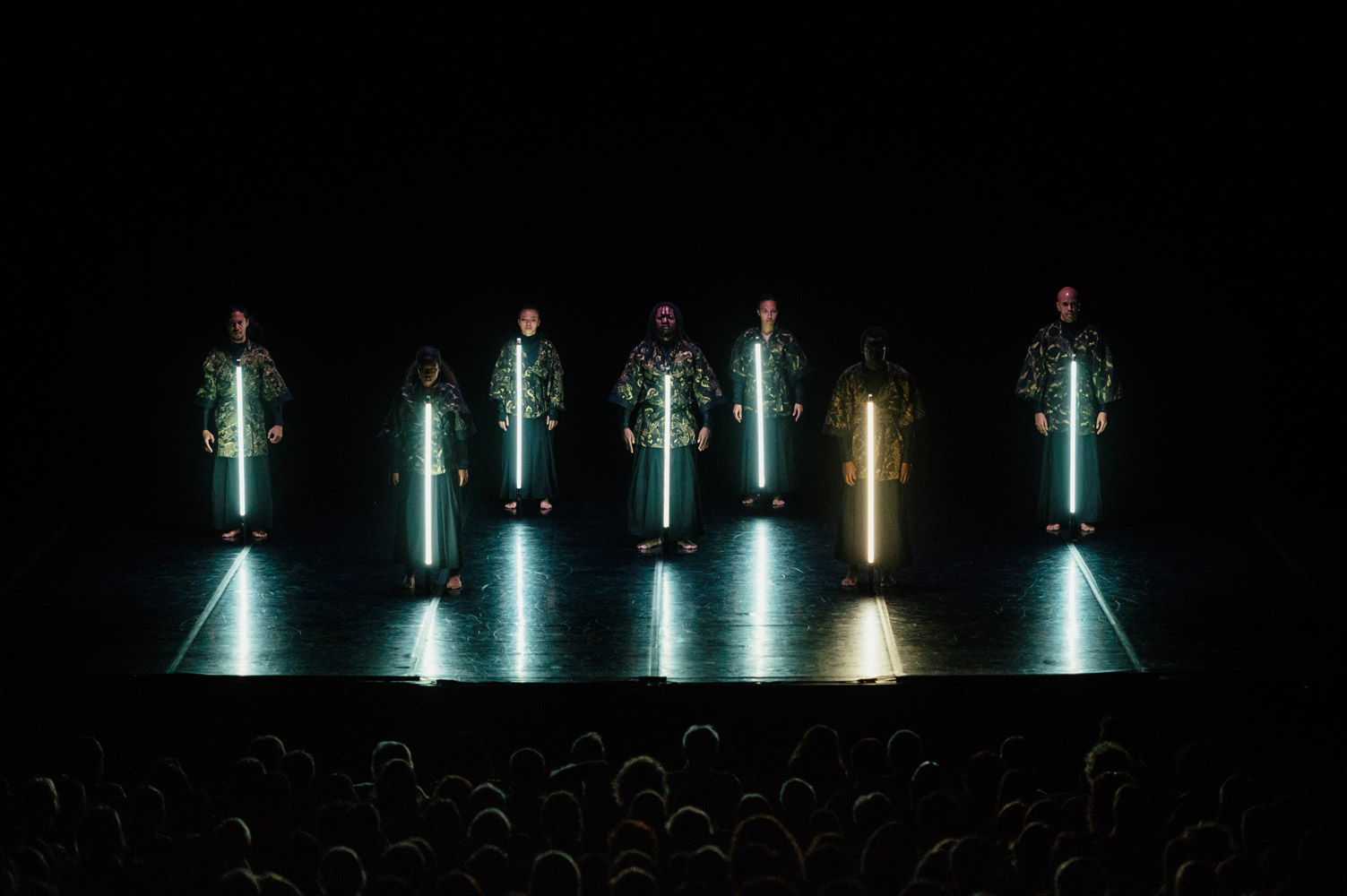

«Yasuke Kurosan», Grand Auditorium, September 2022.

How was this project, Yasuke Kurosan, created? How did it come about, what did you want to express?

In 2006, I saw an Afro-Samurai manga on TV and went searching on the internet. When I typed in “afro-samurai”, I came across the story of the African samurai, Yasuke Kurosan. Ten years later, France celebrated the cultural year of Japan. I went to see a lot of exhibitions, a lot of events about Japan, and I wanted to do something about Japan – because I love Japanese culture, I love the world of manga.

I started thinking about how to make a project about Japan, mixing African and Japanese influences…

What were you doing at the time? Design or dance?

After the year of Japan, both, actually. I left [École Nationale Supérieure des] Arts Deco in Paris in 2012 with a graphic design degree and, in the final year of my course, I started doing professional dance. In 2016, I set up my dance company – Vivons. I needed to combine dance and graphic design.

And do something about Africa and Asia…

I started making a lot of posters with these patterns and, as I was already making videos that mix dance and graphic design, I thought I’d make a video on the story of this African samurai. I was really keen to go to Japan, so for a year I planned, saved, worked, saved some more. I invited a photographer friend, Abdou Diouri (who is of Algerian origin but loves Japan, having been there several times), to come with me. I wrote the story in Paris, we started shooting in the studio, I contacted Japanese artists and when I got there we toured – we went to Tokyo, Kamakura and Koné. We shot over eight days.

And what you see in Yasuke Kurosan is the meeting of cultures…

Yes, I was interested in getting to know Afro-Japanese artists. Because, for me, they embody what remains of the encounter with the African warrior who became a samurai. We see them in the film, and I wanted to understand what they’re like, how they feel, if they know their origins, where they stand in terms of dance and art. They’re the so-called blasians.

Blasians?

Blasians, a contraction of black and Asian. They’re called that in Japan, but also in America. Pharrell Williams, for example, is a blasian.

Making the film, in which I come across ninjas, samurai, dancers, and working with these Afro-Japanese people, was a step towards creating the show. I wanted to work with Afro-Asians and I went for it.

Was it a search for your origins or the story of this black samurai?

Both, actually. I was fascinated by the fact that an African became a samurai.

The story is magnificent.

Japan was closed for centuries and the fact that an African became a samurai meant that the warlord Oda Nobunaga saw some cultural similarities there.

I’ve always said that there are cultural bridges between all the peoples of the world – at the most basic level, we come from the same place; then we go our own ways…

This story fascinated me. This African warrior became another person in another culture and that’s also my story. I was born in France, but my parents are from Mali, so I’m in a country that isn’t my country of origin. How was I able to construct my identity between these two cultures? The samurai is just that – he’s a slave; how did he manage to live between his culture, from Mozambique, which he was forced to leave, and his life in Japan, which wasn’t his culture?

And what he created, what he became.

Exactly. I see myself in this story, because I’m the son of immigrants. How did I become what I am, an artist, choreographer…

Do you feel more French, more Malian, or a global being?

I feel global. But it depends on the situation – sometimes I feel more French, sometimes more Malian, it depends… I feel a bit Brazilian too, because I love Brazil. In fact, wherever I go, I always find points of connection.

Is that what you want to show with the mixed-race dancers?

I wanted to work with Afro-Asian dancers because we rarely talk about this miscegenation. There are very few Afro-Asian dancers.

You found six…

I found three true Afro-Asians; the other three are Afro-European.

Rehearsal of «Yasuke Kurosan», September 2022.

In terms of dance and movement, are Afro-Asians very different from Afro-Europeans?

Yes, yes. When Joyce, Dedson and Felicia dance hip-hop, for example, they dance hip-hop with a martial art type quality. That’s their Asian side.

Can you learn that?

It can be learned. Joyce is Chinese and Gabonese. She was born in China, so she learned traditional Chinese dances and martial arts. Dedson is from Laos and Sierra Leone, but born in France. But when he dances, we see both cultures. And Felicia’s Chinese and Togolese, and has learned Tai Chi… in her dancing, you can see both cultures. And with the Afro-Europeans it’s the same. The French and Cameroonian is different from the French and Malian, or the Guyanese whose grandmother has Thai origins.

And what exactly did you want to show with this crossover on stage?

That each racial mix has its own history, style and energy. And that every mix is unique. That’s what I wanted to show.

We must talk about the music.

Well, there are two parts… Paul Lajus created the music for the film and then Julien Villa created the music for the show. I met him [Julien Villa] on another documentary, L’appel à la danse, about Senegalese dance. We were all dancers and, while watching the film, we started dancing. When this project came up I invited him to participate, expecting him to say no. But he told me ‘it would be an honour to work with you. I love what you do!’

I worked alone for a fortnight in the studio researching links between Africa and Japan, elements of Japanese music – the biwa (a stringed instrument), the koto (a large drum), the corá, the djembê. I asked him to create a layered environment for me, where you go from Africa to Japan and back again, a kind of ping-pong. That’s what you see in the choreography. We’re never on one side alone. We’re between Africa and Asia – like tectonic plates, always gently moving.

We talked a lot and, little by little, began creating things. At the same time, I was working with the dancers. It was a real collaboration.

A parallel creative process…

Yes. I never have any idea of what I want to do [beforehand]. I have intuitions… And since I have a good ear, I can lead the way – more percussion here, and so on. I asked Julien to try to create a kind of orchestral baile funk, like the Brazilian baile funk, but symphonic. He found it a huge challenge. The day he created this… Wow!

Brazil, Mozambique, Japan… This has something of the Portuguese voyages of the 15th and 16th centuries. Do those voyages interest you?

In terms of dance, yes. Travelling means encounters with people, stories, cultures and I’m interested in talking about journeys, making people travel. If we don’t travel, we can’t get to the bottom of things. If I hadn’t gone to Japan, I wouldn’t have been able to create this performance as it is. In Japan, I could feel the energy of the country, the culture, the people. The body holds on to that memory. And when I create, I summon this memory and transmit it to others.

It was in Brazil that I decided I was going to become a choreographer.

Was it?

Yes. I liked dancing, but it was in Brazil I decided that, as well as graphic design, I also wanted to dance. So when I got back to Paris, I auditioned with [choreographer] Raphaëlle Delaunay.

But had you studied dance?

No. I’m self-taught. I learned in the street, at festivals…

And on your travels.

Exactly. At festivals I evolve a lot and as each country has its own festivities, I’ve learned a lot.

In your work, you talk a lot about Afro-futurism. There’s also the post-memory movement. What do you feel part of?

I feel like an explorer, an entrepreneur. I like to create things. And because I’m curious, I’m also interested in history, in my history, because I don’t know it.

You don’t know it?

Having been born in France, I learned Malian culture differently, through my family – but you learn best in the place itself. So I did some research. And I went back to Mali with my parents. I took a camera and followed my mother on a ‘tour’ of the village. I became interested in each family’s story so I went back for a month to interview these families. One day I went to see an old man who, they said, knew all the family trees by memory. He told me about all the family trees since 1850 – it’s an oral culture, which is also my approach to things. But things get lost. I learned a lot about my family, my place, my history. And a year after I did that, this old man died.

Was there no one else with that knowledge?

He had shared his knowledge, but by passing on bits to various people; no one had the full picture. It was very interesting to go back in time and get to know people who have a history.

You’re talking about the past and the original question was about futurism…

Yes. It’s important to go into the past, bring it into the present and then create a future.

Going to the past allows me to work on the present and say who I would like to be in the future. When creating shows it’s the same thing. I’m interested in the stories, I create the video or the show, which open up new perspectives, meetings between cultures.

If I had to talk about movements, I would say that I’m a creator of new perspectives, because new perspectives allow reconnection between people, whose bonds have been lost in history, through wars…

Not only due to colonialism.

Yes, I think since the very beginning, but it’s true that colonialism destroyed a lot. I’m really interested in postcolonialism and research on postcolonialism also serves to establish truths and to question things. To lay the cards on the table and talk, together.

Make peace.

Yes, create peace. And show: ‘do you think you’re so different from him? Actually, no, you’re similar, in some ways.’ That’s what I want to show: that through stories, we discover things that make us very similar, even without us knowing it.

Changing the subject, and to finish: light enters this show like a ballerina. Is that your graphic designer side coming into the choreography? How does it all connect?

Through manga and my African culture, I was introduced to animist culture – every plant, every element, every object, has a soul. Here, I’ve taken on a concept from the inhabitants of Dogo in Mali, according to whom the dead and the living have a star in the sky. The stars represent our ancestors, who also have things to say.

I often say that I never dance alone. I dance with the invisible, but within the invisible, who is it I’m dancing with? With my ancestors, with the light. And in this dance, we communicate with these ancestors.

When I create a choreography, I create images, a picture, graphically. Light is the scenography. It will design something with lines, curves, rhythms, emotion, energy. That’s how I create the choreography. Then I think about how to put it together. Here, I thought: ‘how can I dance with the stars?’ In the show, we dance with the stars. I turn the world upside down to dance with the stars – we grab hold of them in order to continue the journey. It’s very choreographic [conjunction of choreography and graphic] and, for me, ‘choreographics’ is precisely that: poetry.