Discipline, Hide and Punish

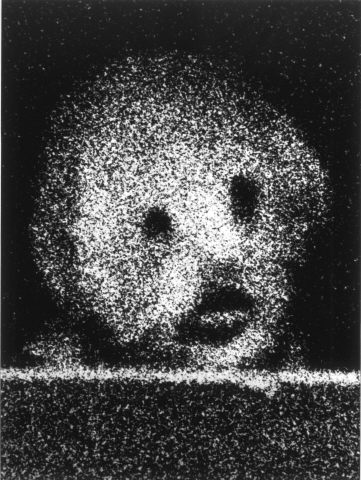

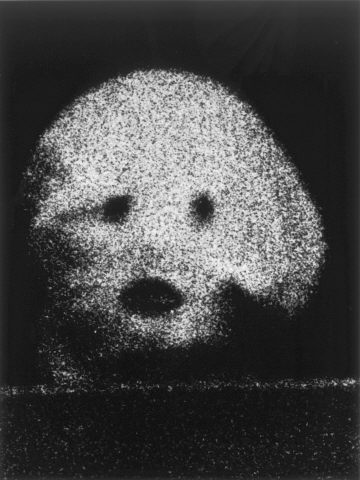

At the start of the 20th century, in Portuguese prisons, the compulsory use of hoods prevented identity and recognition among prisoners. José Luís Neto enlarges the covered faces of each (of ten cases) from the negative of a photograph taken by Joshua Benoliel in 1913, at the time of the official ceremony that brought an end to this rule, making felt, more than seen, the extreme physical and psychological incarceration involved in the method.

While being imprisoned in solitude and total anonymity arouses intense repugnance in the contemporary mind, the voluntary exhibition of the private life on social networks appears to place some at the opposite extreme of community life: but these two extremes coincide in the ‘prison-like’ condition of permanent vigilance.

The work by J. L. Neto and Foucault’s book (Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, 1975) inspired the title of this text and brought about a meeting between the start and the end of the century, which the present exhibition organisation of the Modern Collection facilitates. This exhibition presents works and documents – including pieces that lie on the border between these two types – as well as sporadic changes in its general chronology, for reasons based on the nature, concept and referents of the works. This is the case with this piece.

As Semedo Moreira notes, television reports tend to exhibit success and beauty, as much as the guilt of a suspect or prisoner leads them to hide their face. But the obligatory aspect of doing so inside the prison denies sociability and individuality, which are indispensable to the inmate’s recovery.

The history of the prison systems adopted in Portugal from imported models, in particular the Philadelphian or Pennsylvanian systems (combining the Panopticon with the radial system of constant isolation and permanent vigilance) and the Auburnian system (which combines isolation with communal daytime activities), explains the history of the penal structures adopted in Portugal, for example in 1852, in the 1867 reform and in Lisbon Penitentiary in 1885.

Foucault’s work develops at length the bio-political question of normalisation and control, setting out the history of the prison and punishments for criminality as an instrument for modifying subjects, in the sense of their social ‘use’: moulding the will, erasing memory, weakening and altering identity, nullifying the gaze of the other as one’s mirror. Comparison with the contemporary situation of permanent exhibition (apparently desired, online and imposed by the georeferencing of all movements and acts as citizens and consumers) becomes obvious. The debate around this form of ‘voluntary servitude’ in a situation of apparent freedom has led to reflection on the present day that can be recognised in it.