‘Art harnesses the infinite potential of the imagination. Any attempt at change always stems from something first seeded by the imagination.’

What made you want to take part in the Youth Advisory Group (YAG)? What were you expecting when you applied?

When applications opened for the Youth Advisory Group, I had just handed in my thesis. I had been working intensively on issues relating to culture: How can art be a form of resistance? How can it be deployed in practices aimed at transforming society? How can communities come together through culture and art to fight for their rights, for change?

I spotted the call for applications at the perfect time. I thought, ‘This is exactly what I’m doing at university.’ During my studies, I realised that restricting my activities to the academic sphere simply wasn’t enough. I wanted to engage in these issues in real life, in the real world, with real people and with my community – the people around me in Lisbon.

I saw that the Gulbenkian, an institution of considerable stature, was engaging with the very area that I was interested in – art as social transformation – and that it wasn’t afraid to talk about transformation and the impetus for change. I thought there might be an opportunity for me to get involved.

Did you have any experience of the Gulbenkian before the project?

I’m from Porto. I only came to Lisbon three years ago. I was studying abroad on the Erasmus programme for a year, so it took me a long time to have any contact with the Gulbenkian. Like most people, my first experience of it was visiting the garden.

I’d never been to CAM, so it’s interesting to question whether I may have had certain expectations or preconceived ideas of it, without actually having experienced it in person. It’s a bit like starting from scratch, with only some external information. I had been to a few exhibitions at the Gulbenkian.

At university, we had a course on the political dynamics of the Middle East. And the opportunity arose to visit the exhibition ‘Tudo o que eu quero’ [‘All I Want’] as a group, about the history and erasure of Portuguese women artists. To have an insight into the role of women in this world, including Calouste Gulbenkian’s wife. Such issues are fascinating, because they also allowed the academic community to move into a space that it had not traditionally occupied. It made me more eager to get to know this place.

Earlier, you were talking about the importance of art as an agent of change. How do you see art as working in this way? How can art be that vehicle?

Art harnesses the infinite potential of the imagination. Any attempt at change always stems from something first seeded by the imagination. And art has the potential to exist in the collective imagination. As such, it can serve as a way of dreaming up new possibilities for the future.

It isn’t hampered by limitations; it’s very free. There are no prescribed canons. What’s more, art is always influenced by our daily lives and our reality. Even though there is this concern with neutrality, art is always highly political, as it’s immersed in the social and human aspects of our world. So I think art has a transformative potential that is easily understood by everyone, and easily disseminated by everyone, too.

In your application letter, you mentioned that you are very involved in human rights groups and activism. Do you think a cultural institution like CAM can play a role in this area and, if so, in what way?

Institutions bear the weight of being established structures, of dealing with red tape, and of acting as systems rooted in practices that, by their very nature, prolong the existing regimes, because it is those regimes that give rise to the institutions themselves. I think that our role, whether as members of CAM’s Youth Advisory Group, as young people or as individuals, is to try to challenge such structures in order to breathe new life into institutions, forge new paths and open up new possibilities.

When young people like us use this space to ask questions, it can become a space used by immigrants, by racialised groups, and by people of all kinds, making the Gulbenkian a more inclusive and diverse space. It doesn’t make sense for a cultural institution to shy away from responding to current problems. In other words, for the Gulbenkian to be an important foundation with real-world relevance, it has to be inherently concerned with human rights, migration issues and equality.

The YAG is dedicated to thinking about issues that affect young people. What should young people expect from cultural institutions?

People are increasingly expecting to see the real world reflected within the walls – physical or otherwise – of cultural institutions. They want such spaces to pay heed to current topics of discussion and the voices and issues that have a platform in the outside world.

The very issue of the representation of people and systems. The democratisation of access, in terms of both physical access and access to a proper understanding of artists and audiences. This question of who really gets heard and represented is a very important one, and not just for young people.

We young people are probably more vocal about these issues. But I think that, even unconsciously, visitors to these places want to feel both welcomed and challenged.

The YAG has been running for several months now. What have been your highlights so far?

Firstly, the openness shown by all the teams. I hadn’t expected that. The enormous amount of dialogue, the openness to criticism, and all the constructive comments and praise. This exchange of information is what drives things forward.

I also appreciate the Live Arts area. The term ‘live arts’ didn’t tell us a lot about what this actually covers, especially as it doesn’t translate all that well into Portuguese. The obvious assumption was that it focused on theatre or music, which I’m not that familiar with.

But then we discovered that this broad term, and the programme associated with it, encompasses conversations, poetry sessions and many other manifestations of live arts. When you’re not inside the cultural or institutional bubble, you don’t really know what it means.

A lot of information from the Gulbenkian, and indeed any other cultural institution, easily gets lost in translation for audiences that aren’t in the know. So we always look closely at this issue of communication and the language used.

This quest for language – let alone the ‘right’ language, because I’m not sure we’ll ever get there – will always be tricky. It’s about being at ease and having the scope to analyse and question, because dialogue can give rise to construction and change.

The fact that space is given over to such dialogue here is very important, and it was something that surprised me. We were able to hold a session with Foundation staff, for instance. I like the way that there was scope for things that hadn’t been specifically planned as part of the project. The trip to Évora to meet with the Board of Directors was very eye-opening.

We identified issues, such as the gardens, that had not been considered in the strategic plan. For those who are familiar with the grounds of the Gulbenkian, it seems unimaginable that something so important, and so associated with the institution, would not be given due consideration.

And then there’s everything else we’ve discovered, including the size and composition of the teams themselves. A lot of the teams are made up of very young people – we hadn’t realised that this was the case. There were a lot of women on certain teams, too. We made little discoveries like that every day.

The YAG was involved in International Museum Day. This was an opportunity for you to execute something that you thought up by yourselves and unveil it to the public. You were involved in the ‘Silent Party’. How did this idea come about? And even though you weren’t here on the day itself, what did you learn from people’s reactions?

It was the first concrete challenge we were given, so this was our chance to put the theoretical work we were doing into practice. We split up into smaller teams, according to our particular interests and our ideas that we had proposed. This made for a great set-up, as it facilitated an easier and more concrete exchange of ideas between smaller groups.

Everyone was very open with each other and we discussed all of the ideas. Nothing was imposed in a hierarchical way. It was wonderful to work on an equal footing like this. We felt free to suggest the DJs ourselves, in the case of the ‘Silent Party’, along with the possibility of having a collaborative playlist and including young people, queer people, women, and so on. This inclusivity was manifested in the choice of DJs and the emphasis on participation, with the express involvement of the public through the collaborative playlist.

Small-scale tweaks like this had a large cumulative impact, both on us as a team – we were delighted with the way the project and our ideas were received and the way we were treated within CAM itself – and on the audience, which got fully involved and benefited from the experience. I think this duality of participation and reception is a wonderful thing. And that’s were true change can take place.

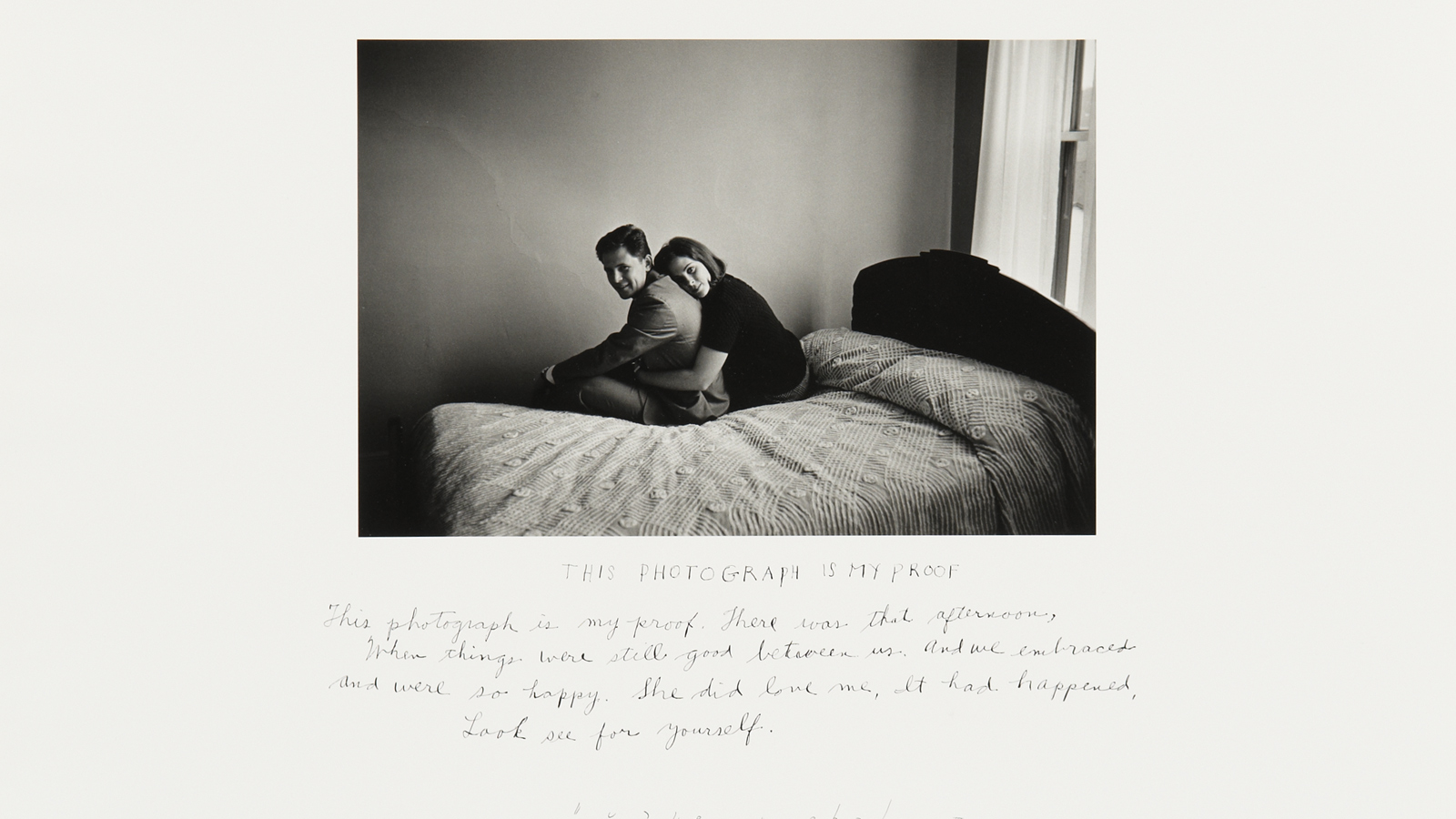

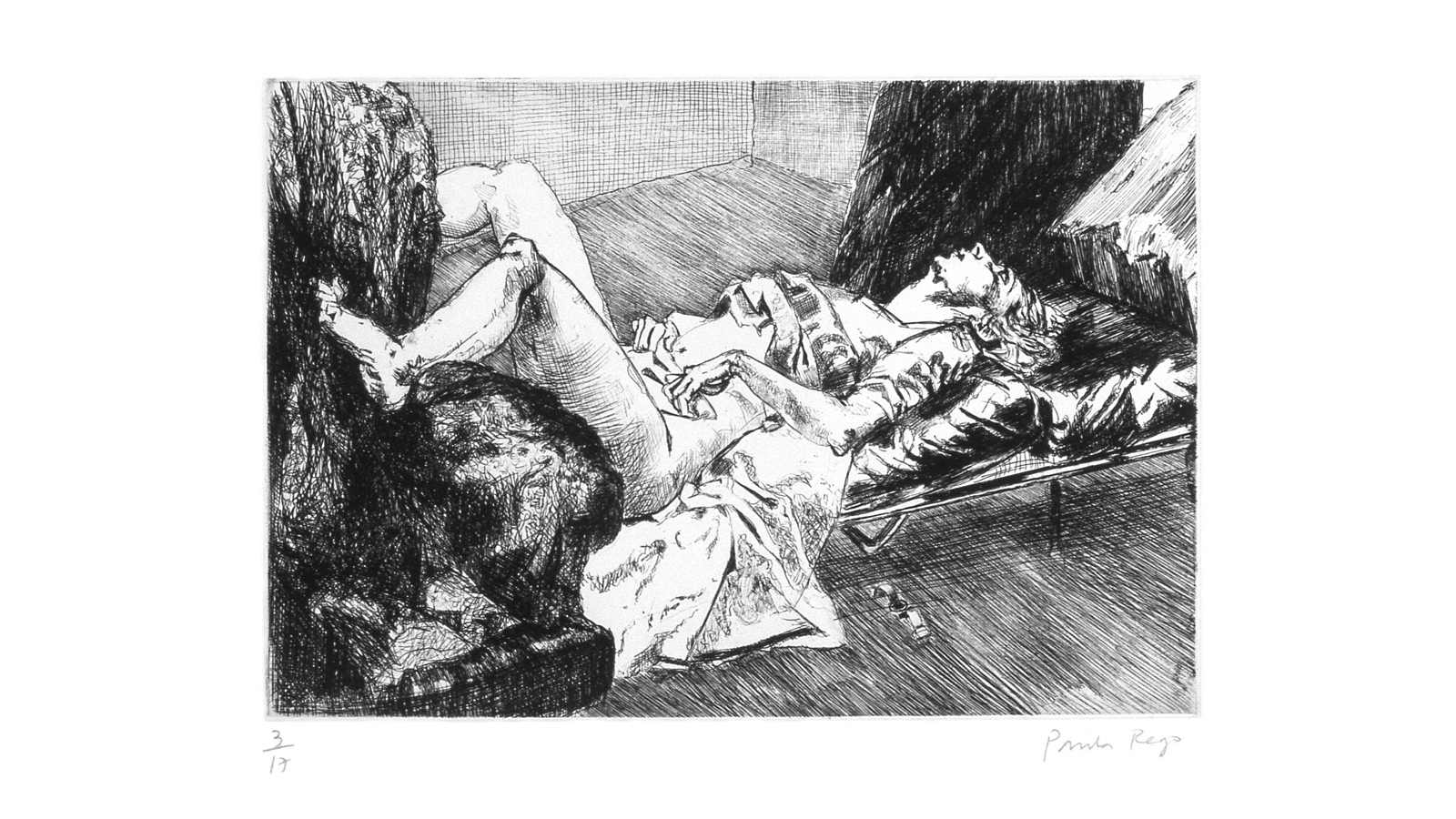

At the start of the YAG project, you were asked to choose two works from the CAM Collection. You chose one by Paula Rego and another by Duane Michals, ‘This Photograph is my Proof’.

The second piece reflects my more romantic side. Things often disappear, morph and change, leaving us with a memory. These remain as traces in art, idealised yet constructed physical manifestations.

Besides its aesthetic genius, Paula Rego’s work also has a highly political dimension. This is a work about abortion, an issue that remains as timely and important as ever. The artist’s bravery and resistance come across through her art and were so pertinent at the time she produced the piece. Although years have passed and sweeping changes have taken place, there have been a great many setbacks along the way. The importance of these works lies in the fact that they will always speak to us. We mustn’t go back to the way things once were.

To finish off, I’d like to ask you about your expectations for the reopening.

One thing that interests me is that we haven’t all had the same level of contact with CAM. I feel that if we were all already familiar with how CAM worked, we would all have very similar expectations, and our work would also turn out very similar. These differences are very telling.

For me, CAM embodies the potential for transformation. To use the new building and all the architectural innovation as a metaphor, we can also carry that spirit of transforming mindsets and participation across to the level of art and society. Making this place a truly participatory institution that is open to all audiences, not just a few, and that really wants to hear other voices is vital. The Youth Advisory Group is proof of this process of listening, of willingness to change. The various community curation events that have already taken place also exemplify this ethos.

We’re always asking for more such initiatives and support. CAM is already demonstrating the openness that is required. I hope it continues to do so and keeps growing and becoming the change, as a beacon that both illuminates and communicates the transformation that is taking place in society and in other institutions. After all, if one institution does something, and it’s effective, more institutions will follow suit. I think it’s going to be a huge catalyst for change.

Suggestions

Book: ‘This Arab is Queer’ (ed. Elias Jahshan), ‘Your Silence Will Not Protect You’ (Audre Lorde)

Film: ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ (dir. Céline Sciamma), ‘Derry Girls (TV), ‘Hacks’ (TV), ‘Fleabag’ (TV)

Music: ‘Do my thing’ (Erika de Cassier), ‘Rosa Rubra’ (João Não, Lil Noon), ‘Países que ninguém invade’ (A garota não, Luca Argel)

Artist: Maria Zreiq (photographer), du.algo (illustrator)