Around the idea of mask

“Persona originally means “mask”, and it is through the mask that the individual acquires a role and a social identity.”

— Giorgio Agamben

The search for a mask, that is, for an identity, did not always have negative connotations: in ancient Rome, individuals would strive to obtain a mask, for the purpose of social recognition. This ‘mirror’ or ‘recognition of their personhood’ was, for a long time, the way personal identity was recognised. However, as Agamben tells us, there was a fundamental transformation in the second half of the 19th century that would alter the idea of identity: the attempt to identify repeat offenders. Thenceforth, it was not others who guaranteed this recognition, but ‘biological data’, in other words, fingerprints.[1]

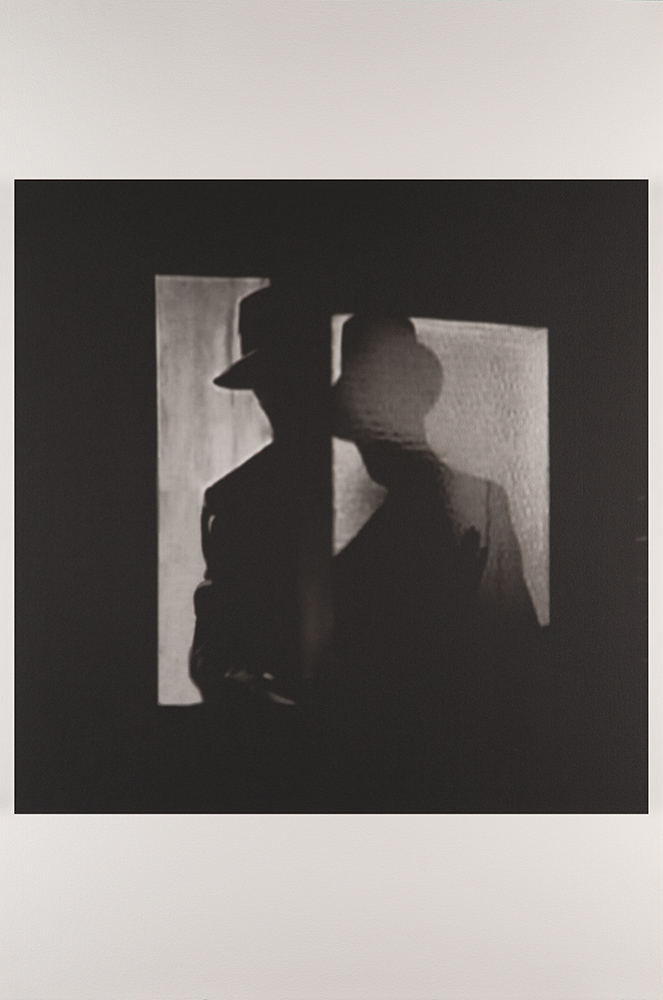

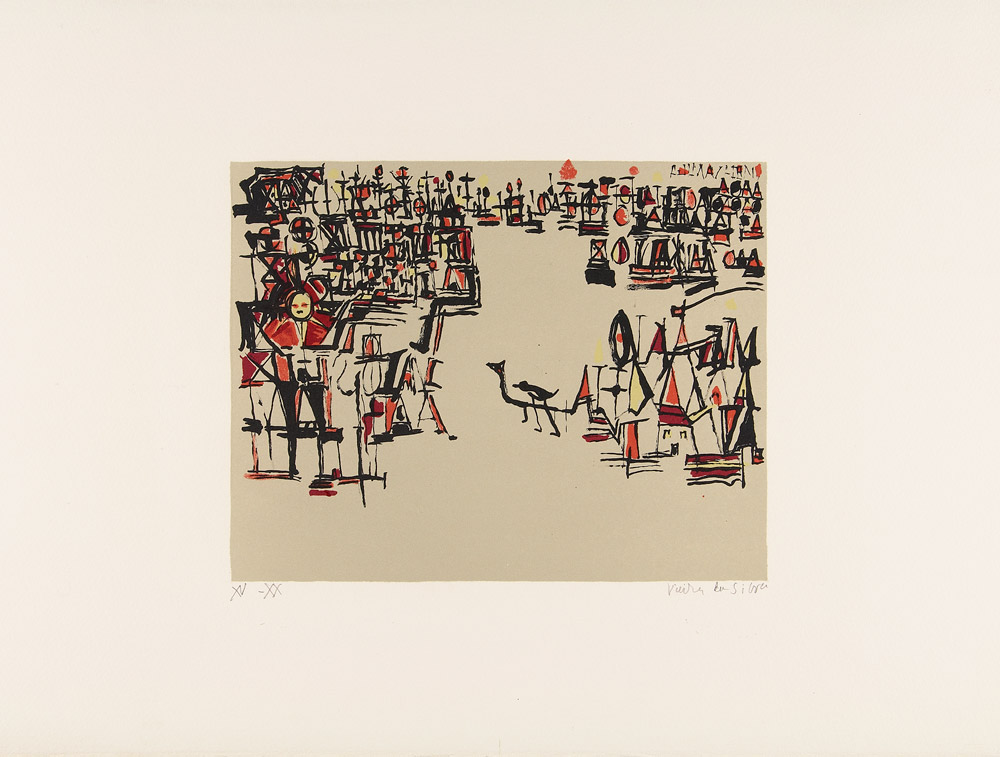

The situation of double identity and double meaning is not very common in the work of Jorge Molder, but to a large extent justifies the reference to duplicity as a central feature of his work.

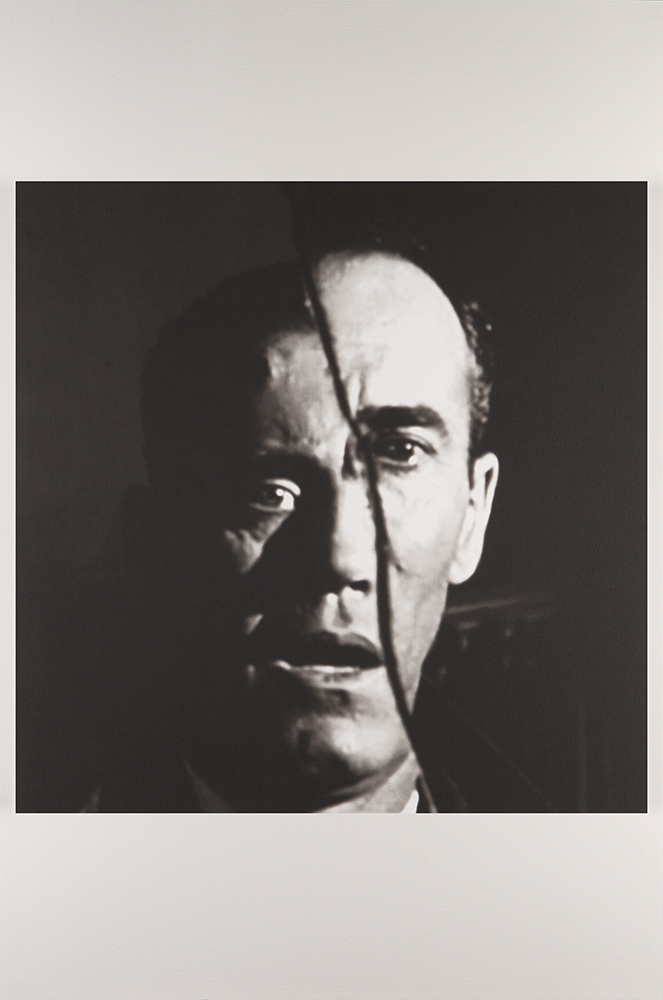

In the series Não tem que me contar seja o que for [You don’t have to tell me whatever it is], composed of 32 inkjet print photographs, there are direct references to film. The work in which we can see the reflection of Henry Fonda, in a broken mirror, refers to the film The Wrong Man, from 1956. Here the mirror is an exemplary element of Molder’s work which reveals precisely this duplicity and fabrication of a copy, envisaging and questioning the problem of the image as a double identity.

The multiple masks approach, which in turn creates the false illusion of multiple identities and memories, reflects the current state of the persona.

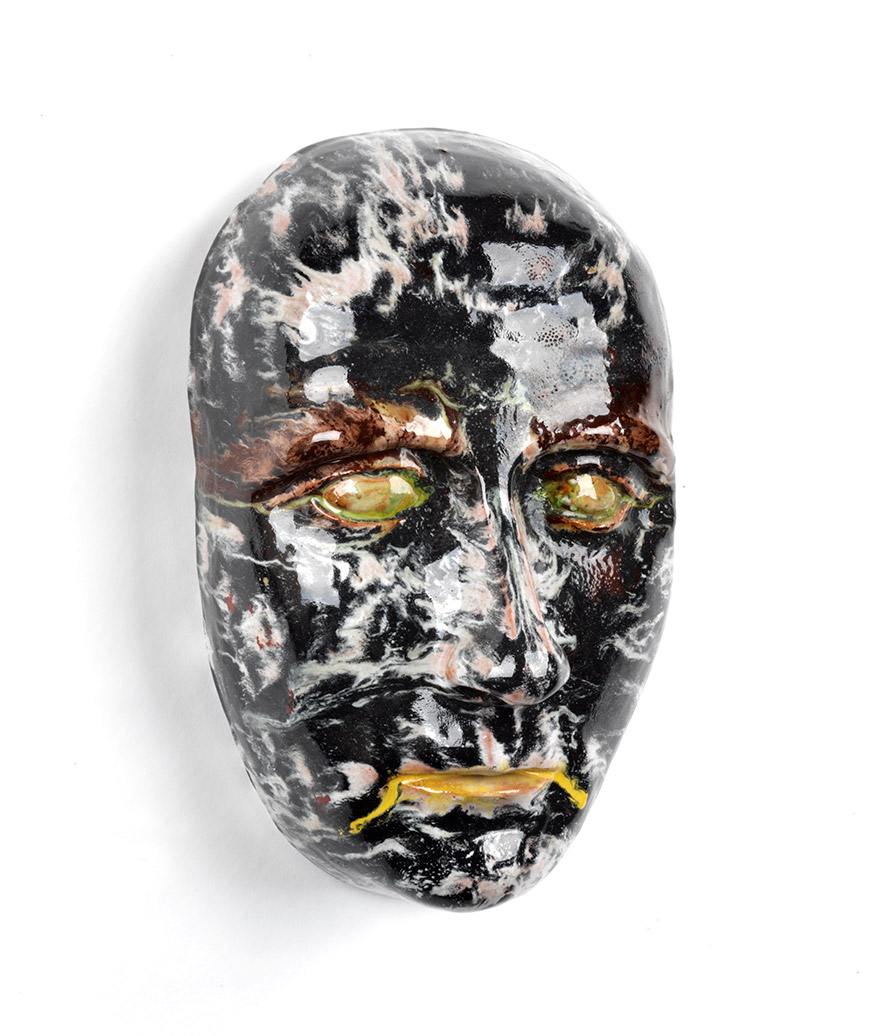

Hein Semke also sought in his work this relationship between mask-portrait-double, both in ceramic pieces – which, skilfully, through mask-faces, represented facial expressions – and by means of watercolours that he produced in the 1950s.

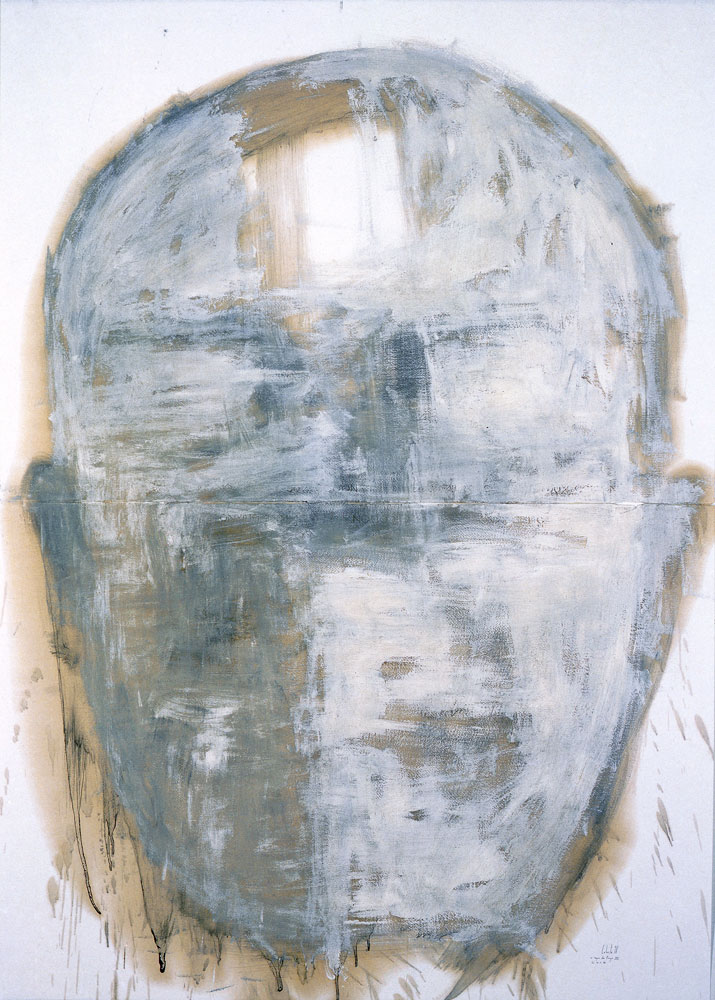

In a more self-referential tone, but still wrapped in a kind of mist, a concealment, a mask, translucent fabrics that make the face appear and evaporate, Pedro Cabrita Reis, in Os Cegos de Praga XII [The Blindmen of Prague XII], represents himself. Although the self-portrait emerges as an erasure – of practically all the facial features – with the clear outline of the cranium, the identity of the subject (for those familiar with the artist’s face) is easily recognised.

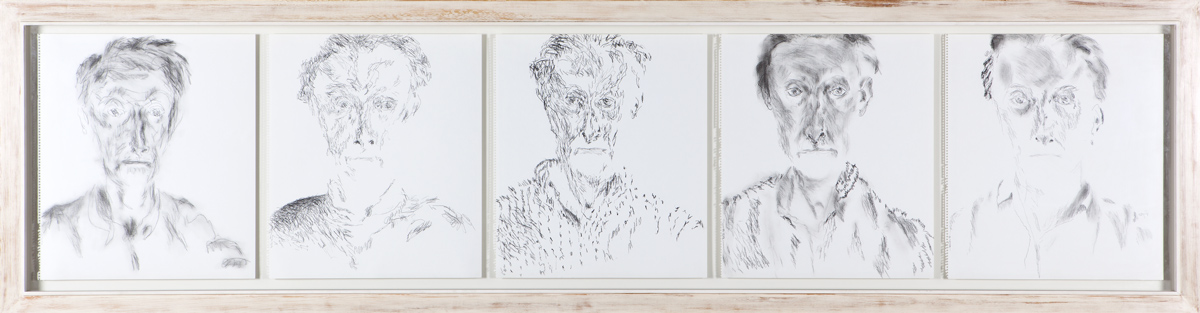

Gaëtan, from 1981, gave new forms to his face in a series of drawings, self-portraits he produced regularly. The way he made them varied: ‘Could they be masks these drawn faces? And as masks could they be theatre masks, carnival masks or funeral masks?’[2] In the five drawings which constitute Troppa Luce, the portraits of the artist are shaped by light and shadow, altering the intensity of the representation, by means of a softer or harder line. The depiction of the face reveals another identity, here also the artist’s persona or double.

In the series entitled Auto-auto-retratos [Self-self-portraits], from 1971 and 1972, Álvaro Lapa introduces the representation of his own body, but focussed on a set of faces. Completed with inscriptions, lines and colours, the depicted faces are also masks or absent visages, the work Voici nos Acteurs being an example of this.

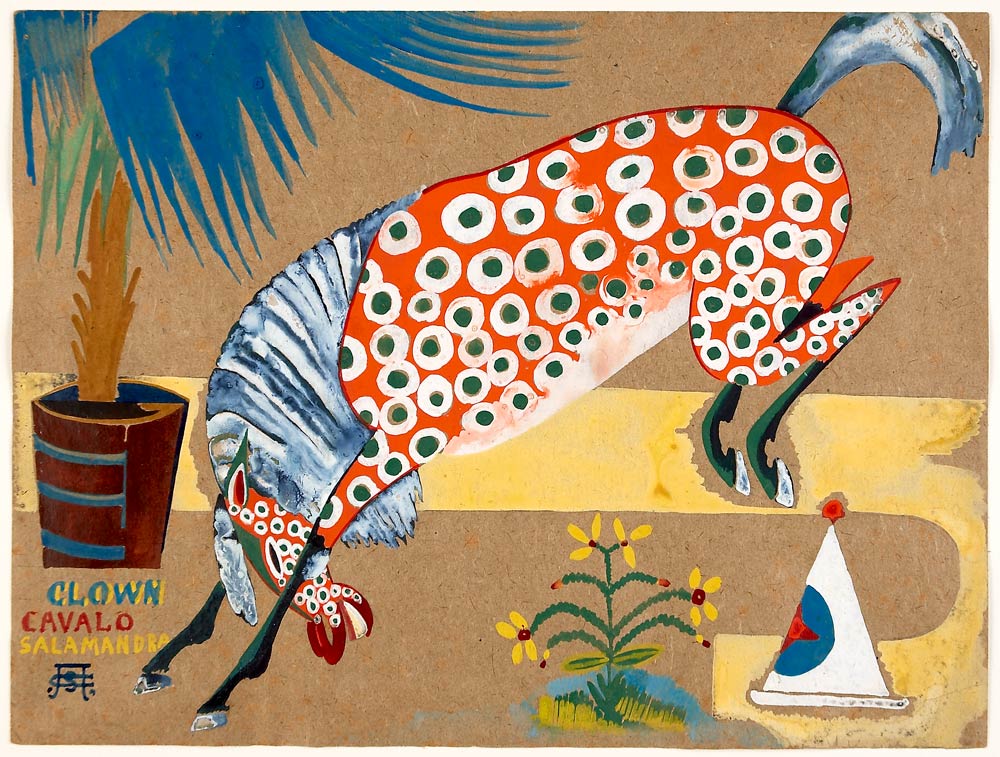

The clown, or palhaço, in Portuguese, is also a persona; considered a living symbol of our culture, the clown goes to the heart of metaphysics because of their exaggeration and extreme simplicity.

According to Burnier[3], the terms clown and palhaço have different meanings, but both have their origin in low Greek and Roman comedy and in presentations of commedia dell’arte. In any case, they seek to lay bare human stupidity and relativise social norms and rules.

The figure of the palhaço emerged in renaissance medieval popular culture around laughter. By occupying the streets, rings, squares and stages, the clown also entered the visual arts, a ‘new place’. Thus, the clown is absent of character, imbued with the reality of humanity. The clown recovers human nature, in their impetuous feelings of joy and sadness, dignity and weakness. Perhaps for this reason the clown has an authenticity: the effect of the mask is predominantly directed outward, creating a figure. By using the mask they reveal instead of hide what is inside of them.

[1] Giorgio Agamben, Nudez, Lisboa: Relógio d’Água, 2009, pp. 61-64.

[2] Gaëtan-Cavaterra, Funchal, Museu de Arte Contemporânea do Funchal – Fortaleza de São Tiago, 1999, p. 5.

[3] Luís Otávio Burnier, A arte de ator: da técnica à representação, 2.ª edição. Campinas, SP: Editora Unicamp, 2009.