Algarve, entre Minho e Ribatejo

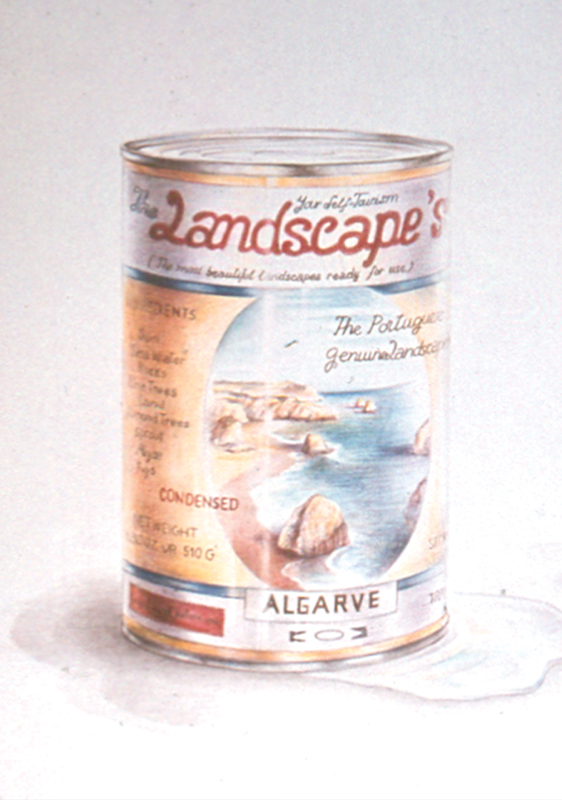

Emília Nadal’s first tin appeared in a drawing made in 1976, entitled Algarve. This work, presented as part of the artist’s solo exhibition at the Contemporary Art Centre of the Museu Soares dos Reis in Porto in 1977, is part of the Landscapes series that also includes the drawings Ribatejo and Minho, both from 1976.

Although Algarve shows all the ironic content that characterised works from the cycle ‘Embalagens para Conteúdos Naturais e Imaginários Liofilizados’ [Packaging for Freeze-Dried Natural and Imaginary Contents], 1976–9, this piece also embodies a certain ‘attitude of revolt’, conveying the urgency of posing questions about conserving the environment in the context of post-revolution social and economic transformations. ‘Attitude of revolt […],’ wrote the artist in 1978, ‘because the first packaging project was a protest against the degradation of our landscape by mass tourism, imagining a tin containing the freeze-dried Algarve coast, ready to use.’[1]

In parodying the interaction between text and image typical of advertising messages, the label of the Algarve tin transforms the Algarve landscape into a ‘genuine’ commercial product, made from ingredients such as seawater, figs, sun, pine trees, sand and more. It is a Portuguese export product, as the words addressed to the consumer are all in English.

The artist’s irony is not, however, limited to this détournement, or to the denunciation of a desire for excessive consumption, the consequences of which threaten the natural environment itself. Indeed, the water spilling out at the base of the tin allows us to imagine a flaw, suggesting that the packaging might not be perfectly watertight, and that any attempt to separate the internal space from the external space, the landscape of package tourism from its broader context – and art from reality – will always find some resistance, a few rebellious salty drops trying to return to the ocean.

Between the late sixties and the early seventies, some key works on the debate around western consumer society were translated into Portuguese. In 1969, the publisher Ulisseia released Everyday Life in the Modern World by Henri Lefebvre. Roland Barthes’ Mythologies and Jean Baudrillard’s The Consumer Society were published in 1973 and 1975 respectively, by Edições 70.

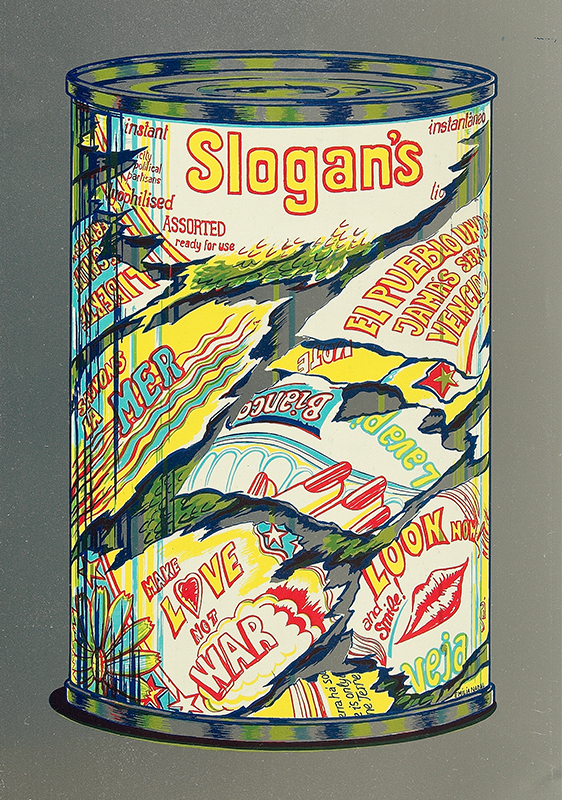

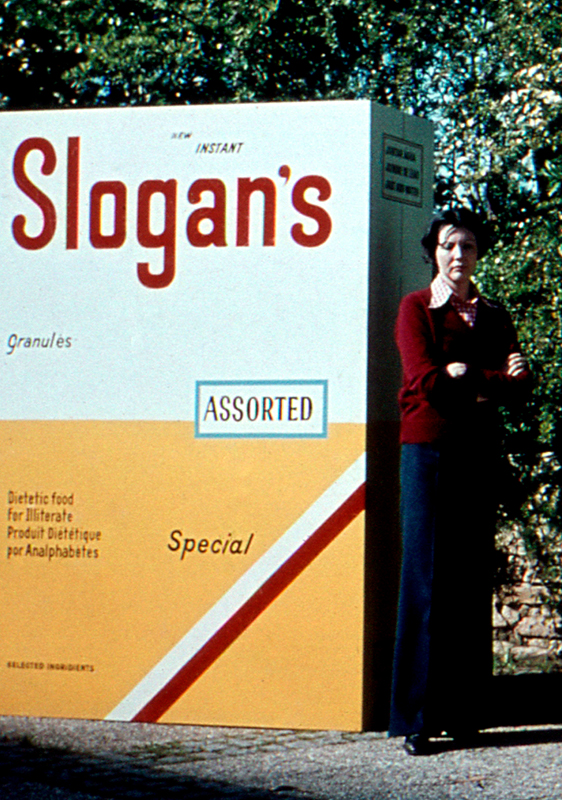

Resonating with these critical reflections were the mechanisms of visual communication that served consumerism and the processes of reproduction of images and objects in the context of capitalist economies, which seemed to be of particular interest to Emília Nadal. Indeed, in 1977, the artist received a one-year research scholarship from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation with an artistic project entitled ‘Visual communication and the multiple.’ It was in the context of this research that Nadal created the tin-object Slogan’s (1979) at the Fábrica Viúva Ferrão, using offset printing on aluminium. To achieve the desired visual effect, the artist made a comparison between old and contemporary label,[2] an archaeological approach highlighting the technical and aesthetic transformations of the visual language used in these supports.

While the relationship between the container and the imaginary contents of the packaging – ideological slogans, tourist landscapes, ideal wives, art, exotic beauties, words, political speeches and others – craftily arouses in the spectator a curiosity or desire that cannot be satisfied,[3] the effect of defamiliarisation is intensified when the tin transforms into an object and is multiplied like a product on a supermarket shelf, for example in Slogan’s.

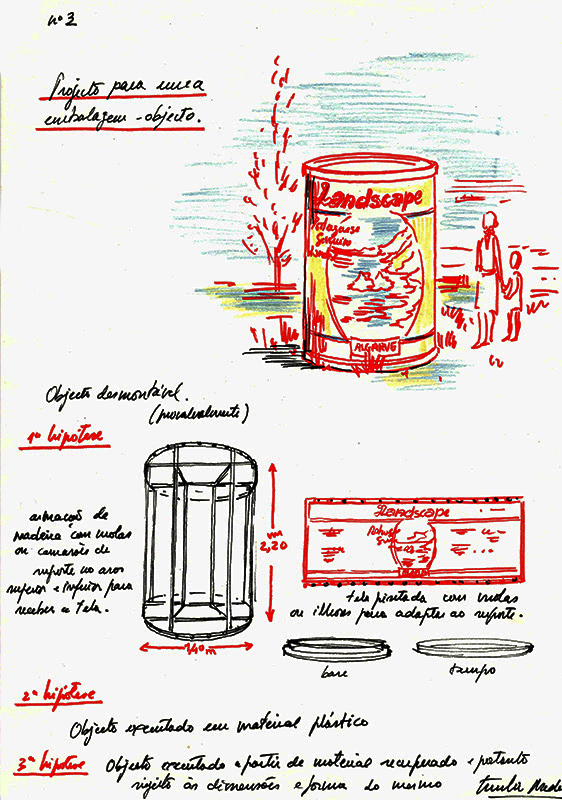

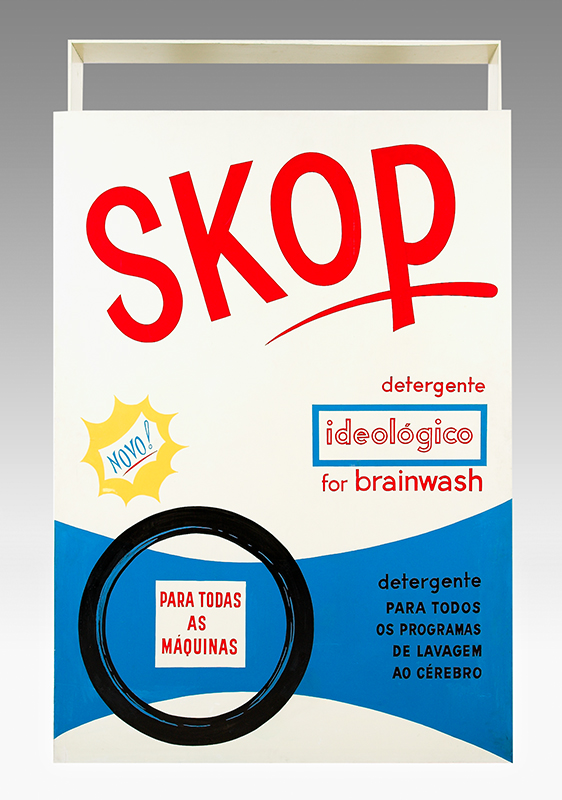

At times, the tins take on dimensions that the artist categorises as threatening.[4] In a sketch from 1978, Nadal imagines constructing an Algarvetin on a large scale, depicting it as a kind of monument to tourist consumption that dominates anyone who lays eyes on it.[5] Ironically, the artist places the tin in the very same natural landscape that its contents contributed to cannibalising. Although this particular project was never carried out, other monumental pieces of packaging, such as Skop (1977), allow us to guess the physical and spatial impact that this piece would have had.

In 1979, Nadal made a second drawing of packaging alluding to the Algarve coastline. Initially entitled Algarve she later gave it the name Allgarve, referring to the brand created in 2007 to promote tourism in the region. This work differs from the 1976 drawing in several aspects: notably, while the publicity message becomes more subtle, the landscape regains more space both on the label of the tin and outside it. It is the colour, however, or the absence of it, that highlights the distance between a product in grey tones and a natural environment in colour, resistant to commercial domestication.

In the post-revolutionary context of openness and of political, social and economic transformation, ecological concerns became increasingly present in Portugal, particularly through the fight against nuclear energy.[6] In this sense, it must be remembered that the works Algarve (1976) and Allgarve (1979), among others, were contemporary to the foundation of the Portuguese Ecological Movement in 1974, the struggles of the population of Ferrel against the installation of a nuclear power station from 1976, and the Festival for Life and Against Nuclear in Caldas da Rainha and Ferrel in 1978.[7]

Although Emília Nadal’s practice wasn’t directly linked to these protests, the artist’s concern with environmental degradation in the context of consumer society crosses paths with the emerging environmentalism of the 1970s. Among the numerous resonances that the artist’s work evokes, some of them widely discussed by critics and art historians over time, the criticism it makes of the consequences of mass tourism in Portugal attests to the disconcerting topicality of her work.

[1] Emília Nadal, Untitled, in Emília Nadal, Proyectos para envases de productos naturales imaginarios liofilizados, exhibition catalogue. Madrid: Galeria Ynguanzo, 1978, n.p.

[2] Emília Nadal, Report on the work carried out with the scholarship, 3rd quarter 1978, 2. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Archive.

[3] The critical literature around these works is vast. We list just a few of the texts that informed our reading below: José Austo França, Untitled, in Emília Nadal, ‘Algumas propostas para a embalagem de conteúdos naturais e imaginários liofilizados’, exhibition catalogue. Porto: Centro de Arte Contemporânea do Museu Soares dos Reis, 1977, n.p.; José Augusto França, ‘Warhol, Nadal e Cª’, Diário de Lisboa. Lisbon: Folhetim Artístico, 27 July 1977; Manuel Rio Carvalho, Emília Nadal. Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 1986; João Pinharanda, ‘Algumas faces de um cristal’, in Emília Nadal, Tudo o Que Acontece 1976-2011, exhibition catalogue. Cascais: Centro Cultural de Cascais, 2011, n.p.

[4] Emília Nadal, Untitled, in Emília Nadal, Proyectos para envases de productos naturales imaginarios liofilizados, exhibition catalogue. Madrid: Galeria Ynguanzo, 1978, n.p.

[5] The sketch can be found in the Grant Dossier assigned to the artist by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 1977. Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Archive.

[6] See Viriato Soromenho-Marques, Metamorfoses. Entre o Colapso e o Desenvolvimento Sustentável. Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América, 2005.

[7] See Nuno Manuel dos Santos Carvalho, A Construção do Ambiente como Problema Social em Portugal: Anos 70-Anos 90, dissertação de Doutoramento em Sociologia. Lisboa: Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2003.