Human Clay

To me Art’s subject is the human clay,

And landscape but a background to a torso;

All Cézanne’s apples I would give away

For one small Goya or a Daumier.1

H. Auden

In 1976, in the Hayward Gallery in London, Ron Kitaj organised an exhibition he called The Human Clay, quoting these lines from Auden’s poem. At the height of minimalist and conceptual art, dominated by abstraction, the exhibition included only drawings and paintings of human figures. In the catalogue text, Kitaj coined the wide-ranging term ‘School of London’ to refer to the group of artists he had brought together. Michael Andrews belonged to this group, which included names that are still well known today, such as Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud, as well as Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff.

To Kitaj, this represented a counter-current of figurative art in the face of what could be regarded as a prevalence of abstraction and artistic languages that did without painting. Kitaj would write ‘Don’t listen to the fools who say either that pictures of people can be of no consequence or that painting is finished. There is much to be done. It matters what men of good will want to do with their lives.’

This phrase was particularly apt in the case of Andrews, an introverted young painter, born into a family with strong Methodist beliefs, who discovered his artistic vocation as a teenager in his native city of Norwich. Between 1949 and 1953, Andrews studied painting with William Coldstream at Slade School of Fine Art in London.

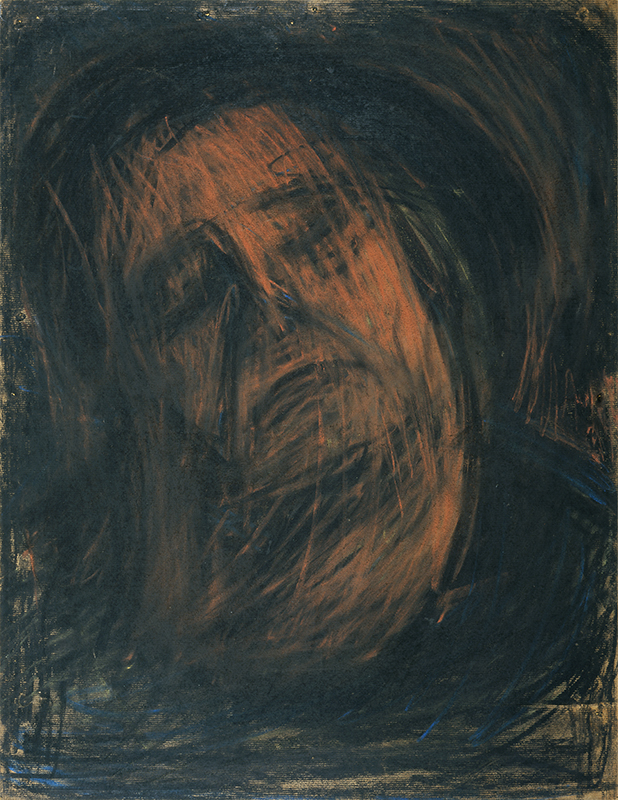

Throughout the 1950s – and in reality throughout his career – Andrews created figurative painting. Until the end of the ‘60s, this figuration focused on the human figure which, from the early ‘70s, he combined with landscapes and specific motifs, such as capturing the light, painting the air (with the very emblematic representation of a hot air balloon, which symbolised just the sense of human presence) or the sea (with algae and shoals of fish).

But, unlike Kossoff or Auerbach, who are also represented in the Modern Collection and who painted dense portraits saturated with matter and hours of posing, Andrews chose to portray people at a suspended moment of an action, along with the attendant psychological implications. One of his best known paintings, A Man Who Suddenly Fell Over, from 1952, when he was still studying at Slade, was purchased by the Tate Gallery in 1959. This painting is typical of his output during the 1950s, imbued with an existentialist character, a common feature in the work of the various other painters in this group. The philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus and, particularly important to Andrews, Sören Kierkegaard, shaped his artistic sensibility.

The change towards the representation of scenes featuring larger groups, formed of people encountered and observed at social events in London – Andrews contributed to immortalising the Soho bar ‘The Colony Room,’ frequented by Bacon, Freud, Auerbach and Victor Willing, husband of Paula Rego, among others – took place in the 1960s. The painting that marked the turning point in this change is The Family in the Garden, in which he depicts his parents, siblings and grandmother in the garden of their house in Norwich.

The group are in a walled garden, a hortus conclusus, at the family home. They are seated. Andrews’ father appears in the foreground, followed by his brother, in profile, and his sister, shown facing the observer. The three figures are clearly delineated. To the left of the composition, and on a more distant plane, we see the less defined silhouettes of the grandmother and the mother, who seems to be dozing on a chaise-longue.

The representation of the fleeting, unrepeatable instant of this image, so particularly meaningful in Andrews’ painting, focuses on the gesture of drinking performed by his brother, the fraction of a second in which the teacup is raised to the lips.

Everyone, except the brother, seems to be concentrating on the pose, on Andrews’ gaze, which coincides with our own, at the moment in which he sketches a first charcoal drawing. Created over two years, the painting can be seen as the negotiation of a suspended moment in Andrews’ autobiographical fiction, reflecting the rigorous, obsessive and meticulous nature of his work.

Andrews referred to the ‘mysterious conventionality’ of his works from this period; in relation to this particular painting, he said that it had been created ‘in peace.’ That peace appears here as a dispassionate statement on his own flesh, momentarily free from the characteristic convulsions of ‘human clay.’

Ana Vasconcelos

Curator of the CAM

- Andrews and his wife visited Paula Rego and Victor Willing in Portugal in the summer of 1964.

- Reproduced in the catalogue for the retrospective exhibition, held by the Tate Gallery – William Feaver and Paul Moorhouse, Michael Andrews, London, Tate Publishing, 2001 –, which served as a basis for the writing of this text and which I recommend reading.

Curators’ Choices

The curators of the CAM reflect on a selection of works, which include creations by national and international artists.

More choices