Marcelino Vespeira

O salto da evidência erótica

Samouco, Portugal, 1925 – Lisbon, Portugal, 2002

Highly coherent, the work of Marcelino Vespeira reveals a pictorial universe that is harmonious, poetic and theatrical, combining precise drawing skills and a sensual palette with rigorous lighting and endless irony and the joy of being. The path that led him to the arts began at the António Arroio School, which he started attending at the age of 12 and where he met Mário Cesariny, Fernando Azevedo and João Moniz Pereira, future surrealist friends, and continued at the School of Fine Arts. Skipping many classes in his first year of the Architecture course, from which he withdrew because of political disagreements with Dean Cunha Bruto, he began to work with graphic arts. He was 18 at the time and worked at Estúdio Técnico de Publicidade, owned by José Rocha, where Maria Keil, Bernardo Marques, Ofélia Marques, Fred Kradolfer, Thomaz de Mello, Carlos Botelho, Stuart Carvalhais, Fernando Azevedo, and others, also worked.

Painting became part of his life early, although not through studies, and was always present in it. In the early 40s, he would go to get-togethers at café Herminius, where he met António Pedro, Pedro Oom, Cruzeiro Seixas, Leonel Rodrigues, António Domingues and Fernando José Francisco. In 1943, he had his first exhibition at the Rua das Flores’ atelier, which he shared with Júlio Pomar, Pedro Oom, Gomes Pereira and Fernando Azevedo. The show was praised by critics.

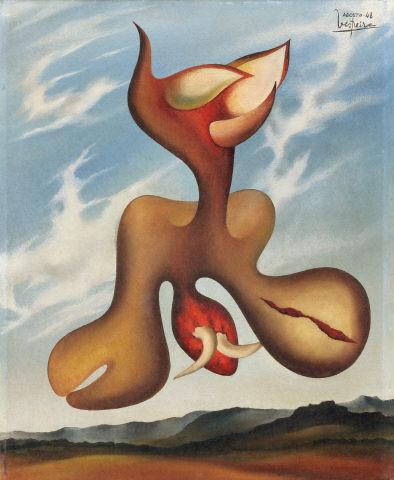

In 1945, the painter recorded his encounter with neo-realistic aesthetics in Apertado pela fome [Squeezed by Hunger], a title borrowed from a poem by Paul Éluard. Exhibited in the first General Exhibition of the Fine Arts, in 1946, this work earned him critical recognition. It was neo-realistic only in its theme (the artist called the brief time in which he was part of the movement as “quickly overcome”), — it presented a formal language of expressionist inclinations — a period defined by Manuela Cruz as from 1943-1947 — , already indicating his future and faithful adherence to the surrealist movement, which would take place in 1947. Since then, without ever abandoning critical sense, irony and sarcasm, his palette has opened up. His paintings and objects express a notorious erotic nature, endowed with great formal, chromatic and lighting sensuality.

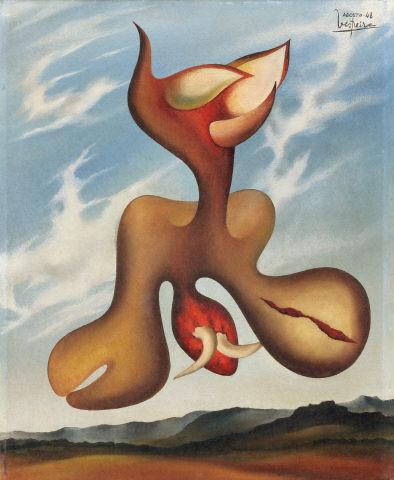

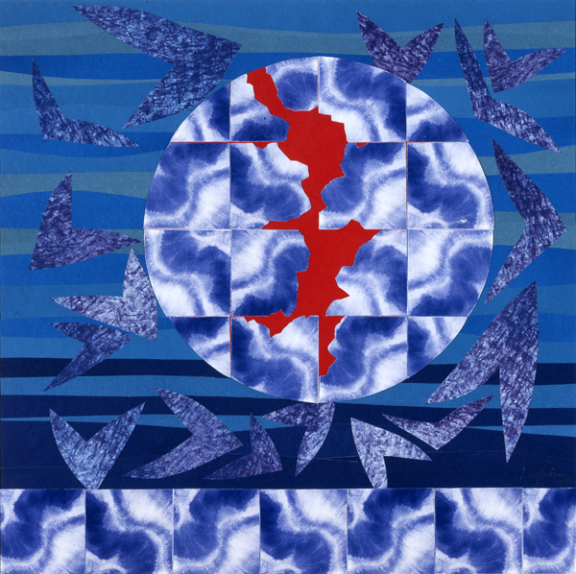

In the 1940s, he moved closer to the surrealists when he met Fernando Lemos, with whom he became “brother-like” friends; their friendship would last until the end. In 1949, he was part of the first exhibition of the Surrealist Group, at António Pedro and Dacosta’s studio. In his paintings, he merged his original imagination with all forms of enchantment experienced throughout life. From the late 1940s onwards, round and pointed shapes combine lines of the female body with the bulls’ (see Simumis, from 1949). We also find floral elements and musical suggestions in his works, relating to his interest in flamenco and jazz. In 1954, he also experimented with geometric abstraction, which fulfilled his taste for compositional balance and symmetry. However, he never stopped employing musical notation. In the 1960s, his composition became more fluid and chromatic, formally preparing his return to the grammar used in his initial surrealist period: a return that happened around 1970. Simultaneously, he continued to work with graphic art. In 1959 (two years after receiving the Columbano prize for a painting), guided by Bernardo Marques, art director at the Revista Colóquio Artes, he started his collaboration with this magazine. In 1962, following the death of Marques, Vespeira replaced him in that position (from which he resigned in 1966).

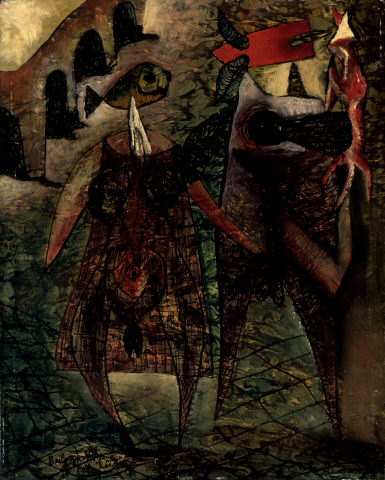

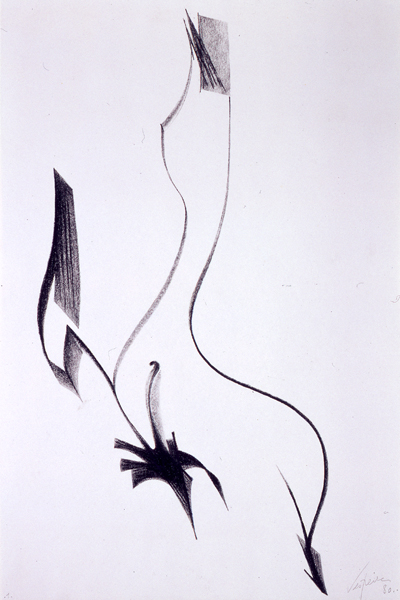

After the April revolution in 1974, he became involved in numerous civic and artistic campaigns, like the painting of collective murals. His line “Fascist art hurts the eyes” became famous as a compact and ironic manifesto of an artistic programme marked by freedom of expression. His sympathy for the Movimento dos Oficiais would lead him to create the symbol of the Movimento das Forças Armadas, the organisation of lower-ranked officers in the Portuguese Armed Forces which was responsible for the 1974 revolution, the military coup which ended the authoritarian regime (Estado Novo) in Portugal. In the early 80s, combined with collage, his drawings synthesize the contours of the landscape and music with the lines of the female body. In 1984, at the same time his works about the garvaia evolved (garvaia is a medieval Portuguese poem that served as theme for poets like O’Neil and artists like Vespeira), he visited the Natural History Museum where he discovered the voluptuous shapes of the double coconut, native to the Seychelles Islands, which led him to explore erotic forms more deeply. In his last years, sickness did not allow him to keep painting, so he worked more on collages. His artwork was honoured by the Montijo Municipality with the creation of the Vespeira Prize in 1985, and by the AICA, which gave him an award in 2000.

Emília Ferreira

March 2013

O salto da evidência erótica

Óleo 131

Óleo 170

Óleo 140

Pescadores da Berlenga

Florirena (Viagem Vermelha duma Flor do Sul)

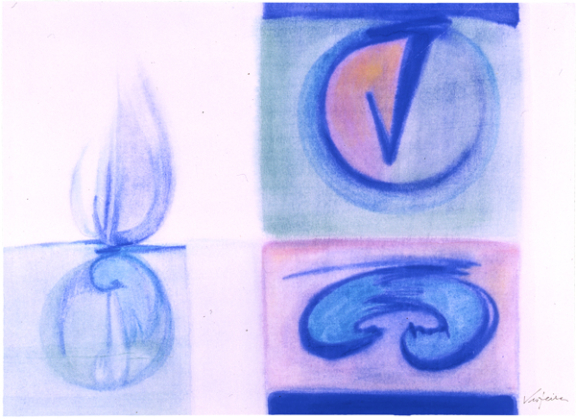

Musagrafia nove

Óleo 54

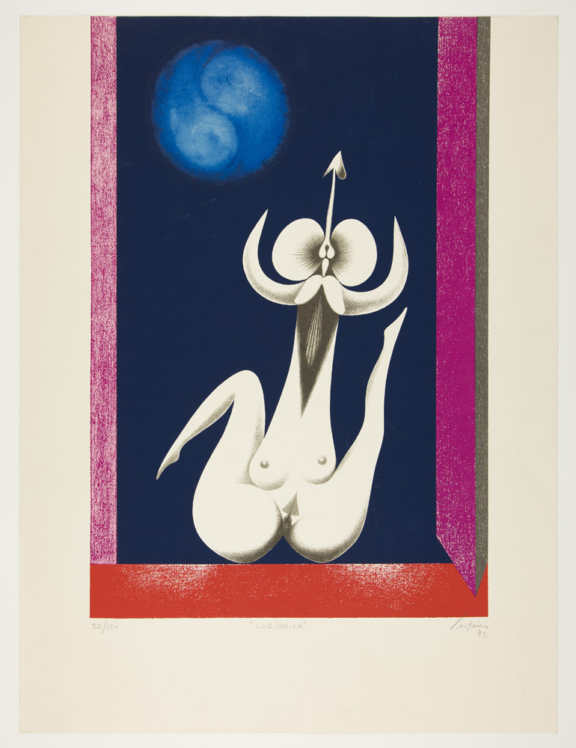

Luzúbrica

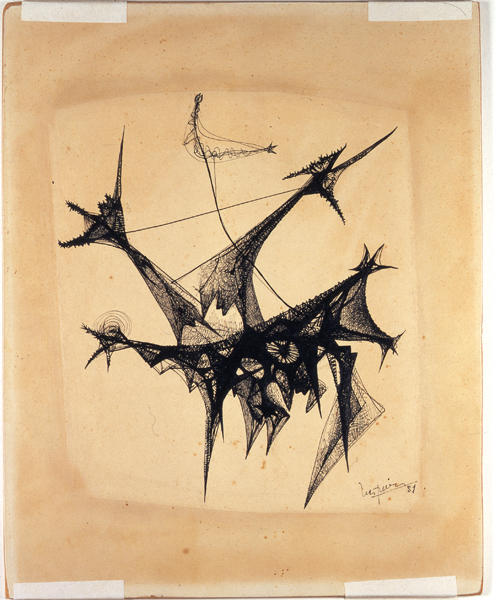

s/título

Covil – de – Abril

Óleo 46

Abrilimagem

Apertado pela fome

Óleo 163

s/título

CADAVRE EXQUIS (1ª Experiência colectiva pelo processo Cadavre Exquis)

CADAVRE EXQUIS

s/título

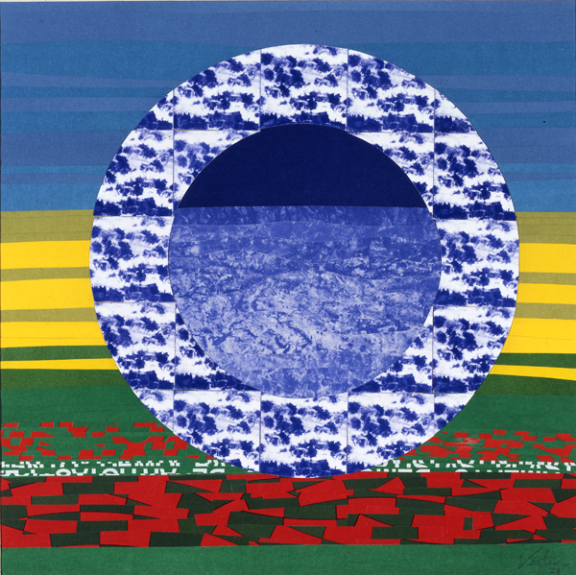

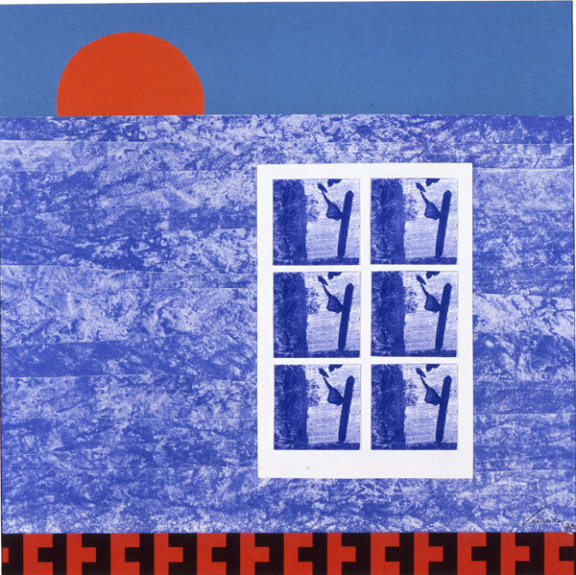

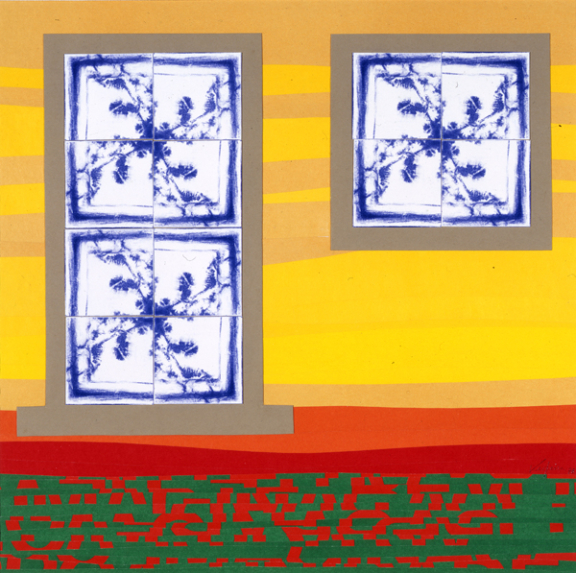

Azulejamor Mãe

Óleo 130

Azulejamor Avô José Vespeira

Azulejamor Pai

Homenagem a Carmen Amaya

Azulejamor Avô Marcelino

Azulejamor Avó Conceição

Azulejamor Avó Margarida

Óleo 105

Simumis

O Menino Imperativo