Joaquim Rodrigo

Estudo

Lisbon, Portugal, 1912 – Lisbon, Portugal, 1997

In the mid 1930s, he entered the Instituto Superior de Agronomia (Higher Institute of Agronomy), graduating in Agronomic Engineering in 1939 (he would later return to this institute, in 1943, to study Forestry). Rodrigo began working on landscapes in March 1938, as part of the team responsible for creating the Parque Florestal de Monsanto (Monsanto Forestry Park), the big “green lung” of the city of Lisbon, under the direction of Francisco Keil do Amaral. He joined the Lisbon municipal authorities as a park specialist and even lived in the Forestry Park with his wife Maria Henriqueta, who he met in 1934. He continued his studies in the 1940s, this time in Forestry. One of the notable public landscaping works on which he worked during this period was the Praça do Império development project, for the Exposição do Mundo Português (Portuguese World Exhibition). This professional activity was reflected in the first works he would produce on the themes of landscaping and the art of the garden (Jardinagem, 1st edition – 1945, 2nd edition – 1955; O Parque Florestal de Monsanto, 1952).

In the 1940s, Joaquim Rodrigo began a cycle of trips through Europe, which would continue throughout his life. These trips – along with the vocation he had already consolidated as a man of the land – would be an important stimulus for the art he created in subsequent years. In 1950, he attended a painting course at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes (National Society of Fine Arts). This was his first attempt to externalise a creative impetus which had been maturing. The experience was nevertheless somewhat frustrating, with the artist eventually distancing himself from the methods and intentions of this teaching, deciding to go it alone, at his own risk. Very soon after, in 1951, he set up his own studio with companions he had met at the SNBA, where, interestingly, he would come to exhibit his work for the first time, in this same year. The desire to paint would remain with him ever after. The knowledge gained through his trips and visits to museums allowed him to structure his painting on solid theoretical foundations.

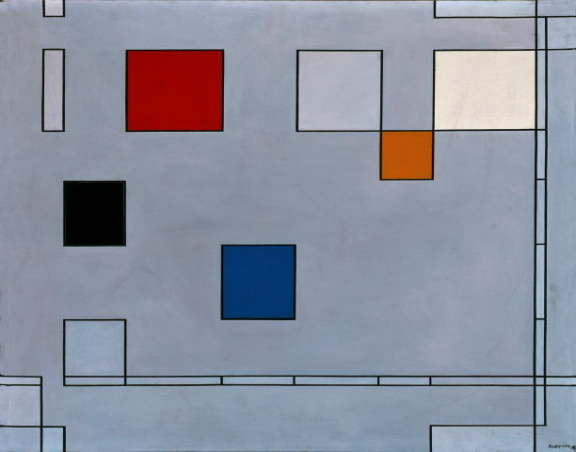

Having witnessed the blossoming and public projection of the trends of abstractionism (and also expressionism) in Paris, he revealed a surprising understanding of pictorial rationalism, which he was able to apply to his original works characterised by an economy of straight or curved lines and planes of colour that generate spatial relations of contiguity, balance or contrast. During this period, the artist discovered a particular interest in the heritage of constructivism and neo-plasticism in the visual arts. He was able to approach the informal movement of artists gravitating around José-Augusto França’s Galeria de Março project, which was trying to project abstract art within Portugal and Lisbon particularly, including his very own “salon”, Iº Salão de Arte Abstracta (1st Abstract Art Exhibition), in 1954. Rodrigo would naturally figure in this event, with three pieces, the alphanumeric titles of which already reflected a whole programme of work around serialism and the idea of variation on the basic theme of elementary geometric shapes (triangles, rectangles, squares, circles).

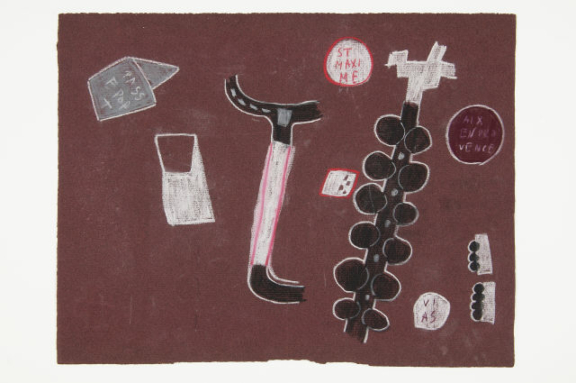

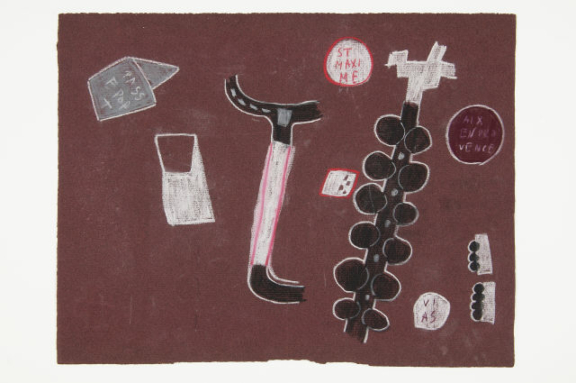

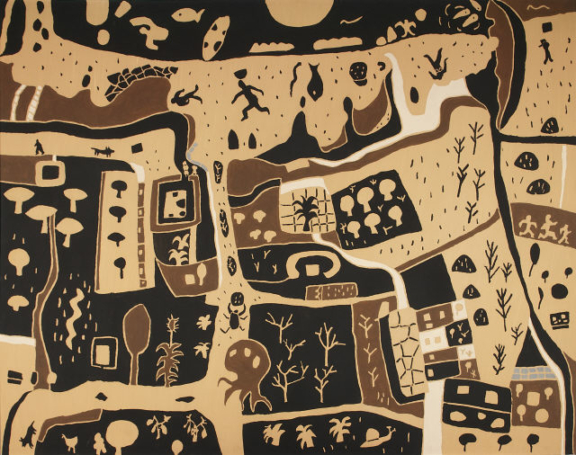

In 1958, he participated in the Retrospectiva da Pintura não figurativa em Portugal (Retrospective of non-figurative painting in Portugal), at Lisbon’s Faculty of Sciences, as well as collaborating as a landscaper on the exterior of the Portugal Pavilion at the World Exhibition in Brussels this same year. The idea of working through variations on basic fundamental elements would continue to accompany Joaquim Rodrigo on his return to figurative forms in the early 1960s. His solar and intentionally naive or childish drawing style (informed by the matrices of European expressionism and Art Brut), would also serve as an apropos for commenting on Portuguese politics in the period of student unrest and political opposition to the dictatorial regime, with the outbreak of hostilities between Portugal and its then overseas colonies. Paintings such as SM (1961) or Kultur (1962) reflect the artist’s attention to the world surrounding him and the total dissention he felt in relation to it.

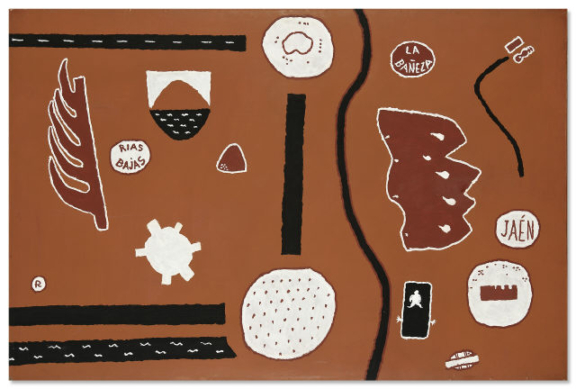

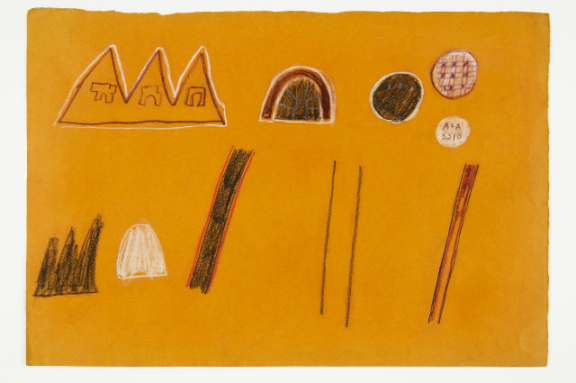

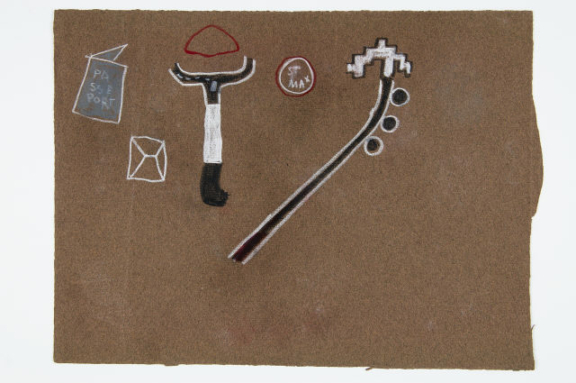

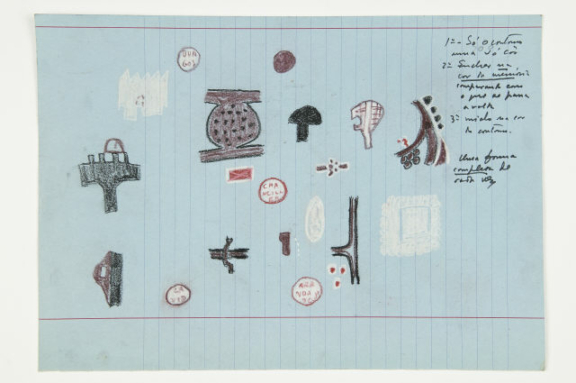

In the second half of the 1960s, Joaquim Rodrigo undertook several landscaping and painting projects: in 1966, he joined Nuno Portas’ urban planning team for the Olivais/Chelas area of Lisbon, working on outdoor space and landscape design. Shortly afterwards, from 1968, there would be an inflection in his painting, moving towards a style characterised by a drastic reduction of iconographic data. Hitherto inscribed in networks or a dense, thin organic mesh, this was reduced to its most economical expression: velvety, homogeneous backgrounds – in earthy or ochre shades – became symbolic territory, favoured for a parsimonious and meditated inscription of graphical and iconographical elements, sometimes organic, sometimes figurative, modelled upon the earth paintings of the Australian Aborigines or African ethnic groups, who he had been studying intently in previous years.

In 1972, he organised a first retrospective of his art at the SNBA (a contact he had maintained and drawn upon on several occasions). This was followed, in the same year, by an award: the Soquil Visual Arts Prize. This was, in a certain sense, the public confirmation of an original way of envisaging art, unparalleled in Portugal, which had first been recognised with the awarding of the Diogo de Macedo National Modern Art Prize, in 1959. Joaquim Rodrigo was called upon several times to join the Portuguese representation at international art exhibitions (São Paulo Biennial, 1957; 1989; Art Portugais, Brussels, Paris, 1967; Triptych Exhibition, Gent, 1991). He left us a profuse and cohesive body of pictorial work, structured on solid conceptual bases (“telemetric painting”, “chromatic differentiation”, “quadro – tipo”), formulated by the artist himself in writings which matured slowly but surely (O Complementarismo em Pintura, 1982; O Pintar certo, 1995). He was also a unique case among his peers in proposing a concrete art, founded on the principles of formal simplicity, balance and depuration. Joaquim Rodrigo knew what he was looking to do – build a science of art founded upon material premises. So intense and meditated was his demand for conceptual rigor that it led him to destroy some of the works he created in certain periods, for example, the cycle of abstract – geometric works in the 1950s.

Ana Filipa Candeias

May 2013

Estudo

Simón Caraballo

Madrid – Vallauris

Lisboa – Algeciras

Vermelho x Azul 2

Composição nº 3

Estudo

Vau – Praia [Vau – Beach]

Estudo

Soria-Nimes

Estudo

Trás-os-Montes

Estudo