Maria Capelo in the CAM Collection

In the hollow of muteness

Lay a word

And raise tall forests on both sides,

Such that my mouth lies wholly in shade.

Ingeborg Bachmann

Secret and silent Iike few others in the Portuguese contemporary art landscape, Maria Capelo’s work has emerged as a slow and persistent visual and semantic construction, akin to poetry, perceived as a process of excavation, reduction and modulation.

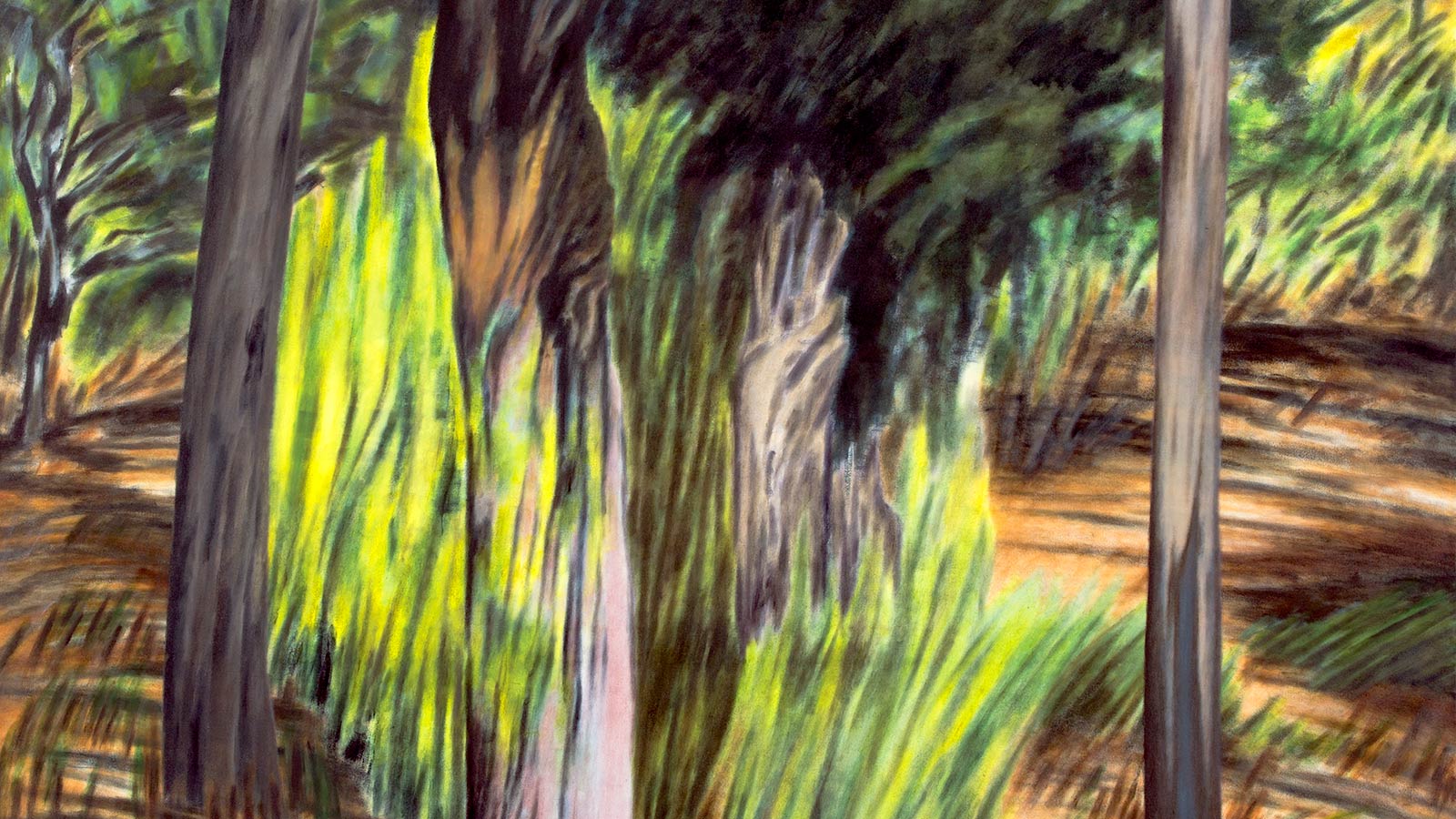

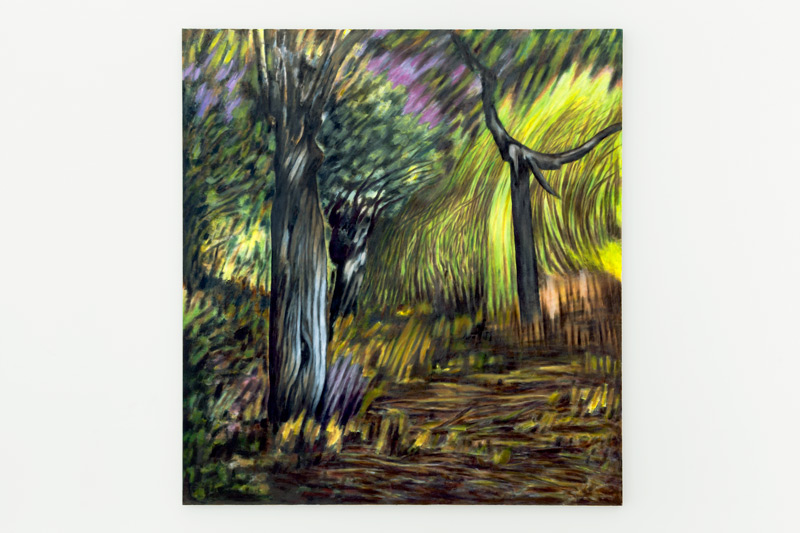

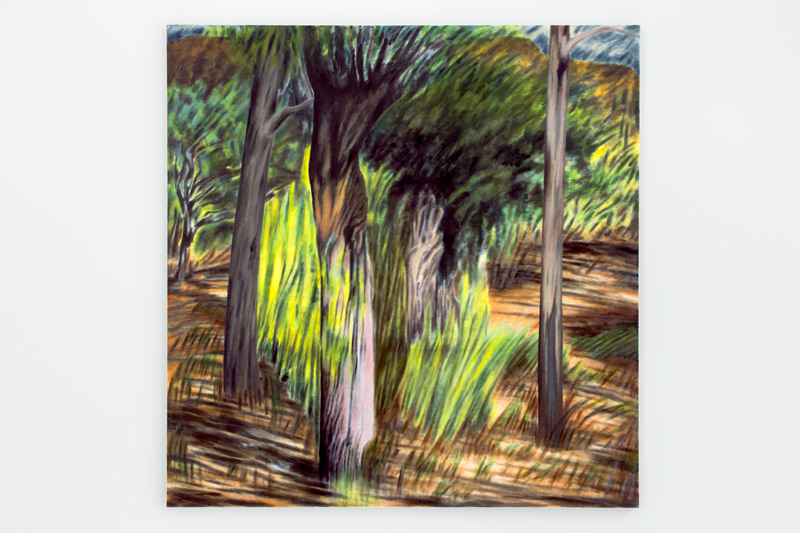

Working with a limited number of elements. including the tree as an omnipresent common denominator, the artist’s paintings and drawings continue the ancient landscape tradition. which has underpinned all artistic production from the West to the Far East.

The landscape is shaped by two kinds of time: a slow geological time, appearing illusorily to precede human activity and to be removed from it, and an urgent present time, characterised by fragility. metonymically announcing the vulnerability of the world and of existence.

The landscapes that inspire Maria Capelo are always real, specific places. The Baixo Alentejo region in southern Portugal, for example, predominates in her work, but Piemonte in northern Italy and Extremadura in Spain are also present. ‘My work is always based on direct observation of things. Even when I don’t work directly on these locations. they are my main source of reference. Isolated. wild places that appear unoccupied but are not abandoned. Disorderly.’

We ask ourselves: why does landscape persist as a genre in the visual arts? According to Orlando Ribeiro, a Portuguese geographer and a leading figure in the modern affirmation of the discipline, ‘the landscape is an historic creation: the traces of everything that has happened are engraved into it. yet at the same time everything is always in danger’. This statement hints at the depth and historic transparency of the theory and practice of landscape.

‘The exaltation that everything can happen, that it already is happening in the landscape around us, and, at the same time, the realisation that every event and action from the past, human or otherwise, has left an indelible mark (‘Wherever you look, a joy lies buried’, a line from a poem by Holderlin that I borrowed to name another exhibition….) is truly staggering to me. And there are other occurrences, as fleeting as passing wind or birdsong.’

Besides direct observation, Maria Capelo also works with photographic records. Photographs contain a dual movement, which contradictory and apparently irreconcilable; they both fix and open up perceptive horizon. For the artist, photographs provide evidence of reality in the immanent, documentary sense of the term. Yet photographs – and herein lies the extent of this asymmetry, inherent to the ontology the photographic image – can also be materials that restore and capture mystery, the enigmatic immanence of nature’s elements, the invisible dimension, the landscape’s sigh.

Today, Marla Capelo’s visual investigation appears to be more urgent and relevant than ever. Today, at a time when we are increasingly obsessed with our precarious existence – is it not that awareness of ourselves as finite beings that has fuelled and carried the practice of painting through to our day when all indications suggest that it should already nave perished? –, the artist’s slow, confident labour, in constant dialogue with other creators (painters, writers, filmmakers) in the great humanist tradition, demonstrates not only the enigmatic nature of our existence but also its beauty and tense fragility at a time when we are more frequently questioning ourselves and how we got here.

Maria Capelo’s paintings affect us in a variety of ways: their human scale invites a physical, body-screen relationship with the image, or better still, with the place created by the image, while they also create a complex space-time relationship, which s hinted at in the (hopefully lengthy) movement/time of the viewer’s experience of the canvas.

Regarding the paintings in the exhibition, the artist explains that ‘trees are the starting point for everything and it is around them that the space on the canvas emerges. ‘The word landscape may be substituted for the word space’ [according to Orlando Ribeiro]. I begin with an element, then another one joins it and power relations arise between them. Once the space exists, it can even destroy them – the trees –, erase them or alter them by changing the scale or the light or by using colour, but without them it would never exist. There is no design outlined in advance, not even a sketch on the canvas. Using the vocabulary that I gather (trees, shrubs, paths), I put it all together gradually, in a slow, patient process.’

As Maria Capelo says: ‘We mustn’t lose sight of the world around us, otherwise the mystery will be lost’.

As Kafka says: ‘In the struggle between you and the world back the world.’

* Text published in the catalogue of the exhibition Tudo o que eu quero – Artistas portuguesas de 1900 a 2020.