Power of the Word II / From India to Europe, The Journey of Bidpay’s Fables

One of the most copied, translated and printed sets of fables trace their roots to the Sanskrit Panchatantra, or ‘Five Treatises’, collected between the second and third centuries CE. The original version, now lost, is claimed to have been brought to Persia by Borzuya the physician to the Sassanid king Khosrow I (r. 531−79) and translated to Middle Persian or Pahlavi. This version is also lost, but was translated into Arabic by Ibn al-Muqaffa (died c. 756−59) and called Kalila and Dimna, after two jackals who are subjects.

The Arabic version was later translated into Syriac, Hebrew, Latin and Modern Persian in the Middle Ages, and then to almost every other language in the world. Jean de La Fontaine (1621−1695), the famous French writer owes much to this oriental book, as he himself admitted, citing the French translation of the Anvâr-e Soheyli, entitled Livre des Lumières, edited by Gilbert Gaulman in 1644, as a source of inspiration.

From its inception, the Panchatantra texts were intended to serve as an educational tool for the ruling elite, a literary genre called ‘Mirror for Princes’. The animal protagonists reflect human characters, with all their noble strengths and weaknesses, each story offering a prudent moral lesson for the reader. Their themes range from deceit and contentment to mortality. Today, some of these stories still resonate with modern society, while others elicit criticism for being outdated; something that was explored by the working-group Power of the Word.

This small exhibition focuses on a rediscovered unbound manuscript from Calouste Gulbenkian’s collection (LA170), with paintings miraculously preserved from the 1967 Lisbon flood. It is a copy of Anvâr-e Sohayli (Lights of Canopus), a Persian translation of Kalila and Dimna by Va’ez Kashefi in the late 15th century, at the court of the Timurid prince of Herat, Sultan Husayn Bayqara (r. 1469−70; 1470−1506). The title derives from the name of Sultan’s commander in chief, Amir Sheikh Ahmad Sohayli.

Our manuscript was copied and illustrated in Iran, in 1842, during the reign of the third Qajar ruler, Muhammad Shah (r. 1834−48). Its fine paintings are very close though to those made under his father, Fath ‘Ali Shah (r. 1797−1834), seen, for example, in the now dismembered Shahanshahnama commissioned by him, in 1810 (now dispersed, in the British Library, the Louvre and other public and private collections).

Fath ‘Ali Shah is even portrayed in our images, appearing in the guise of the royal king. The manuscript might therefore be a copy of an earlier one made for him, yet to be identified, with ours ordered by one of his sons possibly depicted as the young prince in the fables, or perhaps made for the wider commercial market which still held the recently-deceased shah in high esteem.

Anvâr-e Soheyli

In the introductory story, King Humayun-fâl or ‘Blessed fortune’ goes on a hunt with his vazir, Khujasta-ra’i or ‘Auspicious judgement’. The vazir advises the king that to be great he must be instructed by sages, like the fictional Indian king Dabishlim who was tutored by the Brahman Bidpay. This serves as the frame for the book, which thereafter comprises a series of conversations between Dabishlim and Bidpay in which the latter educates the king using the device of moral stories.

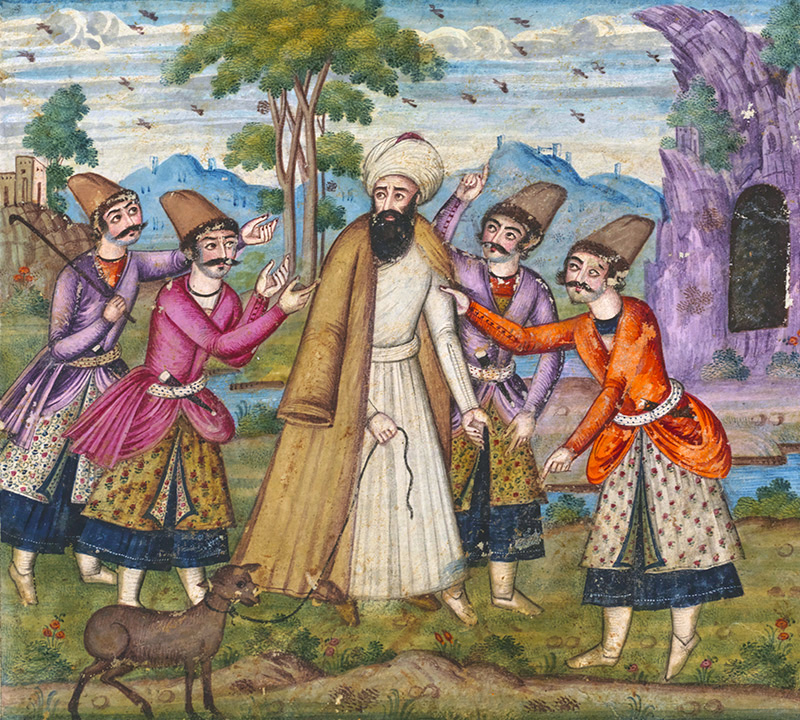

Here we see the first two episodes. In both, the central figure can easily be identified from his long beard and clothing as Fath ‘Ali Shah; thus these images serve as a direct mirror of the prince, picturing him as the major protagonist of the book. Interestingly, Bidbay’s face seems to have been intentionally rubbed out. Possibly the figure portrayed was a contemporary political personality, who had fallen into disgrace, or was interpreted as a saint of some sort and eradicated for religious reasons. Meanwhile, the background reveals a mixture of artistic traditions: on the left, the mountain is formed of Chinese-derived wavy rocks integrated into Persian painting in the fourteenth century, while European shading and perspective are applied to the sky and idyllic rural landscape.

Kalila and Dimna

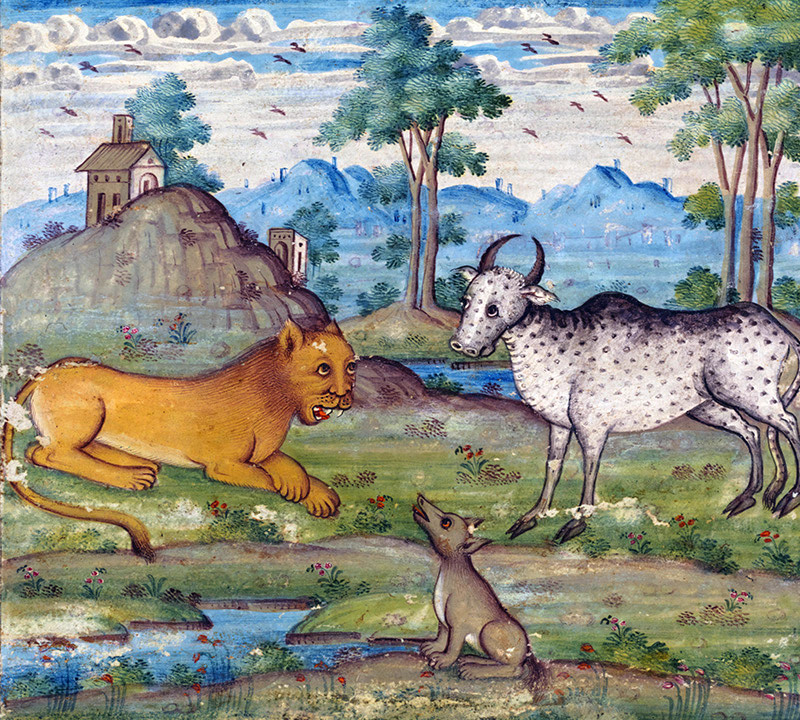

A runaway ox, Shanzabah, arrives at a lush pasture near a forest. The mighty lion king is frightened by the ox’s bellows and hides. Two of his courtiers, the jackals Kalila and Dimna (after whom the Arabic version of the fables is named), worry they will go hungry while the king, paralysed with fear, shies away from the chase. Dimna decides to introduce the ox to the lion. To his great displeasure, Shanzabah becomes the lion’s closest confidant and favourite. Dimna then persuades the king that the ox is conspiring against him, inciting him to kill the ox.

Deceit

A holy man buys a sheep to sacrifice (seen at the bottom). A party of thieves spot him and develop a strategy to steal his sheep. One asks how a holy man can be accompanied by a ‘dirty dog’, while another questions whether he is going hunting with this ‘hound’, and yet others argue about the breed of the so-called dog… The poor man protests that it is a sheep, but they act so convincingly, he ends up giving them the ‘dog’ and returns to the market to try to recover his money.

A merchant’s young wife and a painter in the neighbourhood fall in love. In order to avoid gossip, they hatch a plan for the man to enter the woman’s house disguised in a ladies’ (black-and-white) mantle. Meanwhile, the painter’s slave, having overheard them, takes the mantle and goes to the meeting. The merchant’s wife, in her haste to enjoy intercourse with her lover, does not recognise the intruder. Shortly afterwards, the painter (bearded) comes home and dresses himself in the same mantle to meet his mistress. The latter asks why he has returned so quickly (seen here). Thus, the painter deduces the deceit and punishes his slave, and the hasty woman never sets eyes on her lover again.

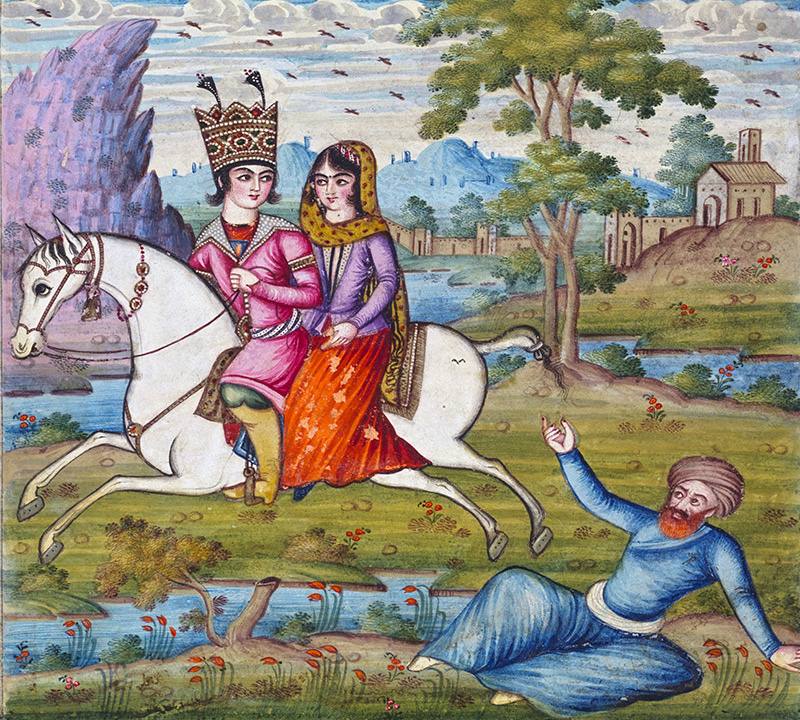

A farmer’s young wife persuades her old husband to leave his miserable farm to go with her to a big city. When the farmer shares his fright at the lechery he may witness there, the woman swears an oath of faithfulness to him. On their way to Baghdad, while the farmer is taking a nap, a handsome prince passes by and as soon as he shows interest in her, the young woman promptly agrees to abandon her husband (here she flies off on the prince’s horse). After a short walk, the couple stop to rest. A lion attacks them and the prince swiftly flees, leaving the woman behind to be devoured by the lion.

Contentment

A poor woman’s cat (black and white) meets a fat, well-fed cat (white) who boasts of feasting at the sultan’s table and takes him there. Unfortunately, the day before the fat cat had created such a mess of the food that the sultan ordered his archers to wait in ambush. The poor woman’s cat, unaware, is the victim of their arrows.

A starving fox manages to find a piece of fresh hide left over from a wild beast’s meal. While taking the skin to his den, he comes across a group of fowls, being watched closely by a man. The fox abandons the hide to catch a fowl, but is beaten by the guardian while a kite (shown here as a magpie) flies off with the animal skin.

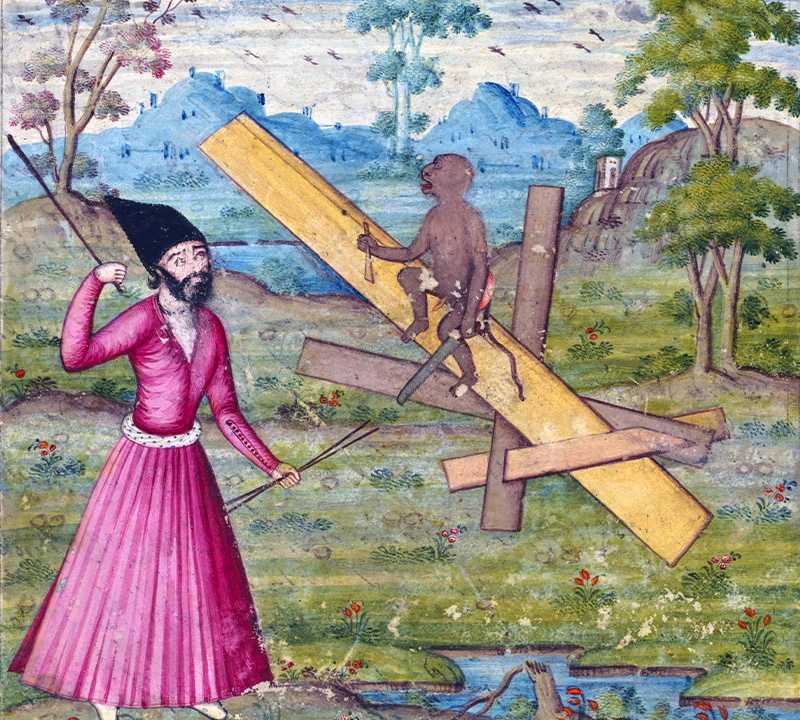

A nosey monkey sees a carpenter sawing timber cleverly using two wedges to aid his progress. As soon as the carpenter leaves, the monkey takes his place, assuming the task is easy. But by taking out one of the wedges, he gets his genitals caught in the cleft in the log, and when the carpenter returns, he is severely punished.

Unity

A crow watches a fowler set a net to catch birds, and then hide. A group of pigeons get caught. They fight desperately to flee. Their king, Ring-dove, instructs them to fly together, all at once. By doing so, the pigeons manage to raise the net into the air (seen here), and fly to a nearby town where a friendly rat comes to their rescue, by gnawing a hole in the net. Ring-dove, who epitomizes a just king, insists on being the last to be rescued, consenting only after all his subjects are safely released.

Ingratitude

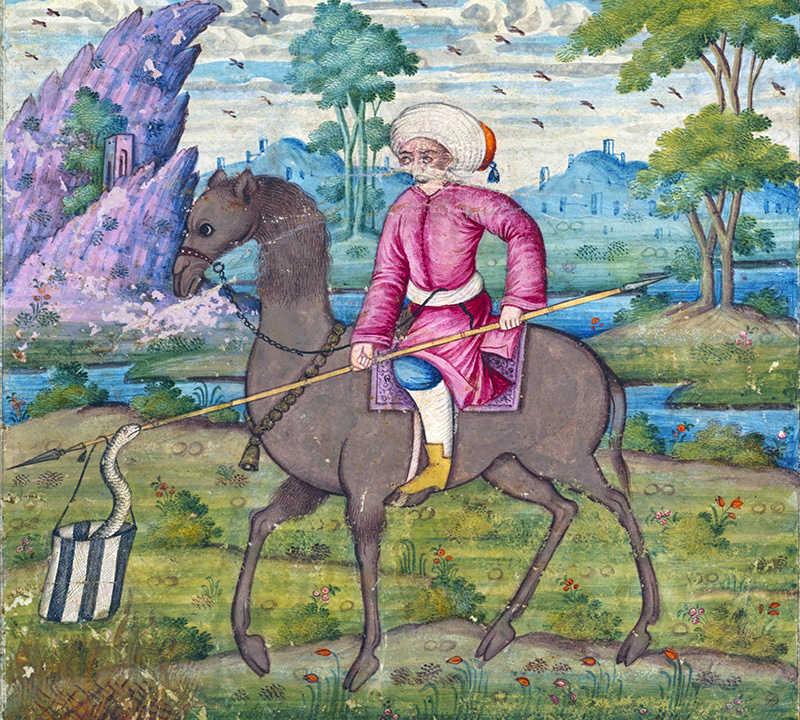

A camel-driver sees a snake caught in a fire and rescues it with a bag fixed to the point of his spear (first image, slightly damaged). As soon as it is released, the snake announces that it will not leave before biting both the camel-driver and his camel. There follows an argument over whether the snake is unjust, or the man foolish in misplacing his clemency. The two agree to seek other opinions. A buffalo cow agrees that in the human realm, the answer to good is evil: ‘over many years I have produced good milk and calves for my owner, but now that I have no more milk he intends to sell me to a butcher!’ A tree then testifies similarly: ‘I offer shadow for travelers to rest in the hot desert, but they saw off my branches’. A fox passes by, and after hearing their stories, says he will answer at the trial only if he can understand how such an enormous snake got into such a small bag (second image). The snake then slithers back into the bag, and the fox instructs the camel-driver to smash and kill it.

Knowledge

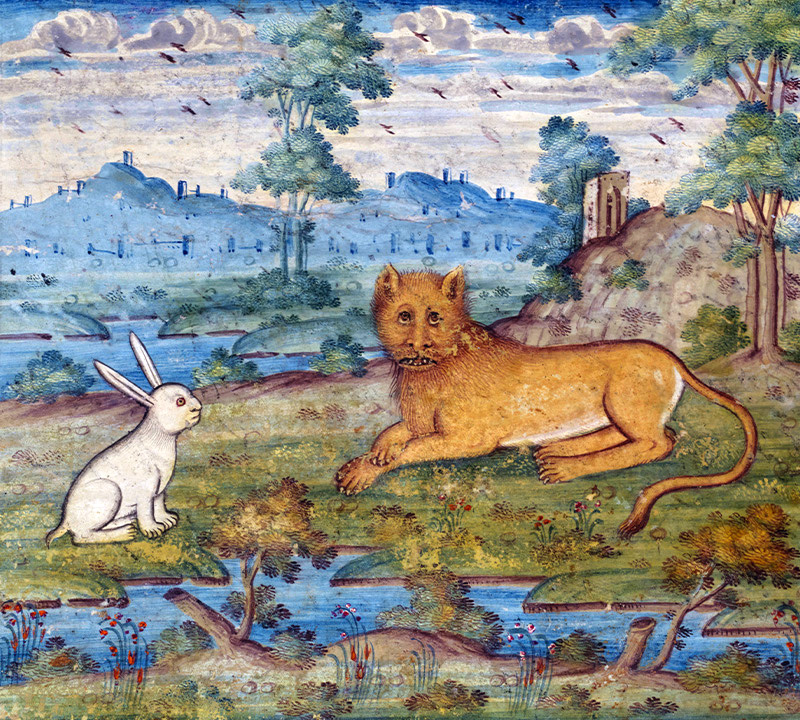

A ferocious lion dwells in a meadow, where the other animals get no rest owing to his persistent hunting. One day, they propose to the king that they offer one willing animal for his royal kitchens daily to avoid the distress and anxiety of the hunt, which the lion readily accepts. Every day the animals draw lots to choose the ill-fated among them. One day the lot is cast in favour of a hare who purposefully delays his arrival at the lion’s den. Angry with hunger and at waiting, the lion asks why he is late. The hare tells him two hares were sent that day, and on the way, they met another lion who caught the first and then hid in a well. The king, furious, accompanies the hare to the well to kill this audacious challenger. The hare asks the lion to climb up onto the ledge of the well (here a stream) so he can show him the other. The king follows and sees a ferocious lion beneath him, clutching a white hare in his claws. He immediately dives into the well and the animals are liberated by the hare’s cleverness.

A poor hunter spends a whole day catching three birds. While trying to catch more, he overhears two law students involved in a noisy argument. When he asks them to keep quiet, they agree but only in exchange for two birds, to the great sorrow of the poor hunter, who reluctantly accepts. Then the hunter asks them why they were arguing, to which they respond: ‘about hermaphrodites, and how inheritance laws should apply to them’. The poor hunter who has only one bird to feed his entire family, then attempts to catch some fish. By chance, he reels-in a beautiful fish, with bright colours, and decides to present it to the sultan. When he arrives at the royal court, the sultan is so pleased with the gift that he orders his vazir to grant him a thousand dinars (seen here). The vazir whispers to the sultan that the prize is totally disproportionate and advises the ruler, who has loudly voiced his intentions, to trick the hunter. He proposes that he ask if the fish is male or female, and regardless of the answer, requests an identical one of the opposite sex before giving the prize. When the sultan presents the question, the old hunter foresees the trick, and remembering the students’ argument, explains that the fish is a hermaphrodite! The king is amazed by this clever answer, and grants the hunter double the previous prize.

Humankind and Mortality

An angel (top right) appears before King Solomon and presents a cup of water for eternal life, offering him the choice between drinking it and becoming immortal or not. The wise king asks the advice of all his courtiers, humans, demons and animals alike. Everyone agrees that their king should live forever; only the heron is absent. When he is summoned to give his opinion, the heron approaches the king (shown here) and asks if he is willing to share this potion with others. The king replies that the beverage has been sent for him alone. The heron responds that he would never drink it to achieve everlasting life, only to witness his friends and relatives steadily dying. Solomon sends the angel away, and declines to drink the potion.

The subject of a king seeking immortality dates back to at least the third millennium BCE, with the epic story of the mythical Sumerian king Gilgamesh. The Greek myth of Orpheus is similar and Ferdowsi (died c. 1020), the famed author of the Shahnama (Persian ‘Book of Kings’), tells a related story about Iskandar, a mythical version of Alexander the Great.

In this painting above, Fath ‘Ali Shah’s features are recognizable in the figure of Solomon, the paragon of the wise and powerful king, able to speak to birds and master the wind and jinns (Qur’an XXVII:16; XXXIV:12-13). The hoopoe is frequently represented at Solomon’s side (here at his feet) and is said to have carried messages from the king to the Queen of Sheba (XXVII:20-28). This bird is also a central figure of the twelfth-century Persian masterpiece, Conference of the Birds, by the mystic Farid al-Din Attar, in which the hoopoe leads the birds of the world on a journey to seek their sovereign, in a metaphorical search for God.

Farhad Kazemi

Guest curator, Institut national du patrimoine, Paris

Coordinated by Jessica Hallett (curator) and Diana Pereira (Learning Department)

Calouste Gulbenkian Museum

Collaboration: Fabrizio Boscaglia, Joana Simões Piedade, João Teles e Cunha, Leila Namazi, Maryam Loutfi, Maryam Nasirpour, Rahman Haghighi, Raquel Feliciano, Ricardo Mendes, Omid Bahrami, Samaneh Sharif, Sara Domingos, Shahd Wadi.

Power of the Word is a participatory curatorial project at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, involving principally Arabic and Persian speakers who join curatorial and educational staff and guest researchers to study the Middle East collection. It aims to enhance our experience of these works by encouraging collaborative research and vibrant, contemporary interpretations which affirm intangible culture.

In this working group, the participants played a crucial role in interpreting the texts and images from different cultural viewpoints, and discussed the relevance of traditional stories and archetypes to our lives today. A panel in the rotation shares cross-cultural aphorisms and contemporary questions that arose during this process.

The project was shared with the public on International Museum Day with the Conference: How Many Voices does a Museum have? and a story for families, The Lion and the Hare.