Beyond the Mirror

Mirrors are particularly interesting objects since they have the ability to transport us to other dimensions, leading us into the realms of spirituality, dreams, or even nightmares.

Artists employ mirrors for various reasons, as they can both reveal and disguise elements of the scenes that are represented. They offer infinite visual possibilities including, most obviously, that of accurately reflecting reality.

Yet even though the chief purpose of the mirror is indeed to faithfully represent appearances, reflecting a coherent vision of the world, this is not always how artists use them. They may focus on ambiguity and fragmentation, in line with their often philosophical intentions, in preference to the mimetic representation of reality.

Curator: Maria Rosa Figueiredo in collaboration with Leonor Nazaré

Consisting of 69 works, a mirror number, the exhibition is divided into five thematic sections, preceded by three preliminary pieces: a sculpture that acts like an invitation to enter, a painting that introduces the theme and a mirrored object that prompts visitors to ask themselves:

‘Who am I?’ Mirrors and Identity

Questioning what or who we are leads us inevitably to look in the mirror. This is because the truth of what we are, or of what we have reinvented of ourselves, can only be found in comparison with the ‘other’. This section includes works that depict situations of confrontation with the mirror [‘water as mirror’, the myth of Narcissus, the ‘mirror stage’], featuring humans and, in a few cases, animals.

The Allegorical Mirror

The mirror as medium for a wide-ranging allegorical tradition, a metaphor for vice and virtues, from Vanity to Prudence, for Profane Love and Lust, but also for time that passes and leads to old age and the inevitability of death, with women invariably the main character.

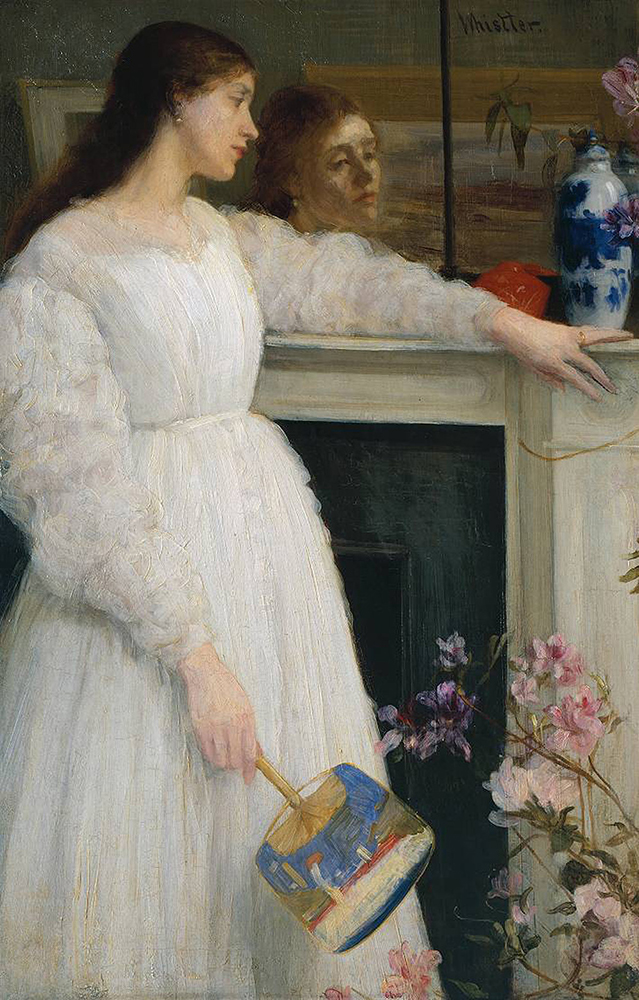

Women at the Mirror: the projection of desire

The idea of privacy is the result of a social construct that has changed greatly over time. While in the Middle Ages the concepts of privacy and ‘puritanism’ didn’t exist, with the female toilet conducted through a ritual designed for a favoured audience, between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries it acquired overtones of an implicit sexuality that was more directly related to seduction. Bathing became less a question of hygiene than a source of pleasure.

In the nineteenth century, with the separation of the public and private spheres, women gained a new sense of privacy in their relationship with themselves and with the ‘other’, resulting in ‘appearing’ taking priority over ‘being’.

Truth and lies within the reflection

Artists have the ability to weave an intricate web of lies within the boundaries of their works. They are adept at distorting, extinguishing and manipulating visible reality, in order to create a specific scenario that is conducive to a particular and wholly imaginary reality.

Anamorphoses – supposedly invented by Leonardo da Vinci, and a popular form of entertainment in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – are a good example of this. Their presence is relevant to this exhibition, since they establish the link between art and scientific knowledge, creating the illusion of a non-existent reality. The use of the convex mirror in painting, used by artists since the fifteenth century, makes it possible to access realities far beyond the field of vision encompassed by the painting. They are like windows leading us beyond the painting and allowing us to discover the inaccessible, as in the famous paintings by Jan van Eyck and Quentin Metsys.

Moving away from scientific artifice, and into the realm of pure imagination, this section includes a number of works inspired by Alice in Through the Looking Glass, namely a painting by Eduardo Luiz and photographs by Cecília Costa and Noé Sendas.

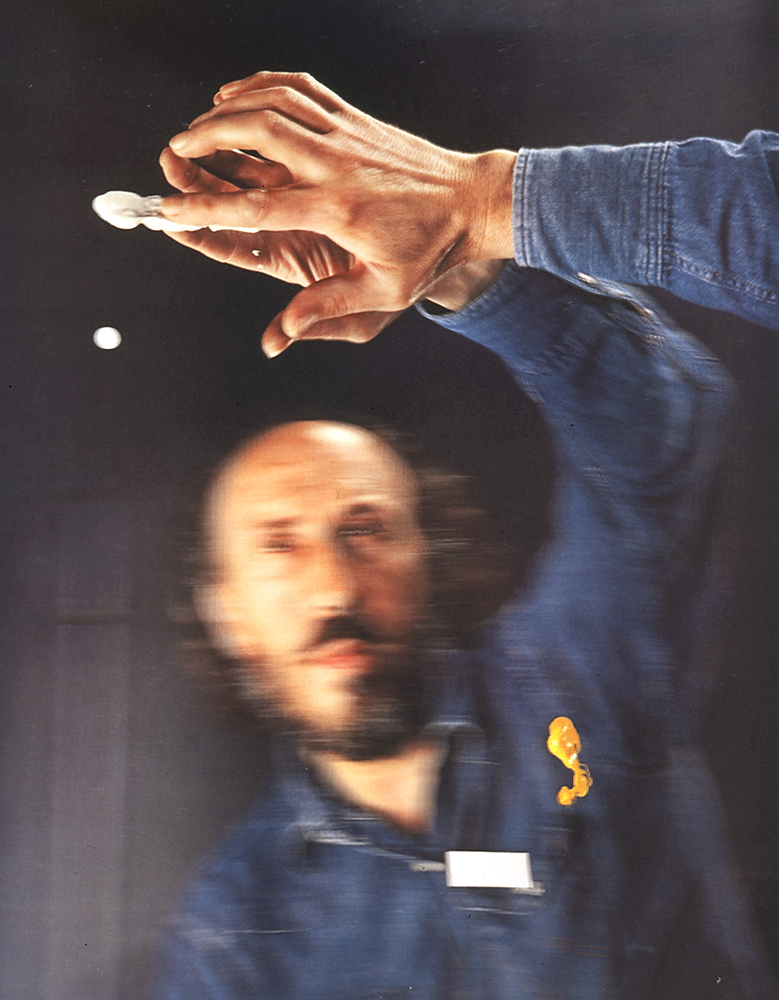

Of Mirrors and Men: self-portraits and other experiments

Although the mirror in painting is predominantly utilised by women, this is not exclusively the case. During research for this exhibition, only one case of the male toilette was found – a man shaving. However, an interesting painting of a place in which such rituals takes place was discovered (The Bathroom of Jacques-Émile Blanche, by Maurice Lobre, included in the exhibition), with its occupant absent and a young girl leaving this private space. In addition, there is a surprising painting by Paula Rego, with a man dressed in a check skirt, a recreation of Eça de Queiroz’s hero, Father Amaro.

Reaching the conclusion that men’s relationship with mirrors is primarily enacted in self-portraits, we selected various examples of this genre for the exhibition. The mirror allows the painter to make a portrait of himself without relying on memory, following a tradition that dates back to the fifteenth century and the birth of the Renaissance.